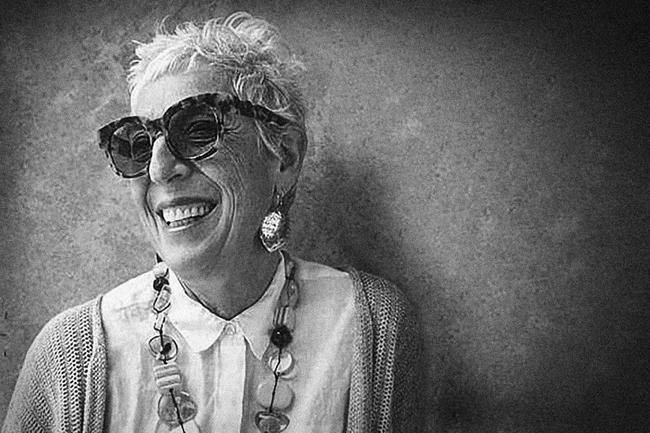

Conversation with

Mariella Furrer

Mariella Furrer has lived in Africa her whole life and is passionate about global human rights. Her images shed a light on some of the world’s injustices and tell moving and powerful stories, which truly connect with her audiences.

Mariella has an incredible talent for making subjects in very tough situations open up to her and share their experiences and vulnerabilities.

She says the most important thing she has learnt about taking good photos is to never lose your humanity for what you’re seeing as that has to be portrayed in your pictures.

Her projects document everything from child sexual abuse and forced migration, to nurse shortages and the wild side of African life. Mariella started her career covering the Rwandan genocide.

How did you end up in photography?

I grew up in a hotel because my father was in the business. I always presumed that’s what I would end up doing, and did briefly go into hotel management in Switzerland. But one day I came across an exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich art museum, a retrospective of Magnum. It blew me away. I just could not believe these photos I was seeing. In Kenya at that time, we all subscribed to National Geographic, which had beautiful images but not as much passion as nowadays.

This Magnum show was very socially conscious and once I saw it, I felt that I really, really wanted to do this. I had just got a camera but had never had one before that. I was 22.

I was advised to attend the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York for a photojournalism course. I then did The Eddie Adams Workshop, which is phenomenal for any young photographer and is where all the top photo editors go. That sort of catapulted my career, as I was awarded most promising young photographer and was immediately on assignments.

Coming back to Kenya at the start of 1994, the UN was pulling out of Somalia. By April, it was the Rwandan genocide. At that time, all the big names in photography and journalism were in South Africa because Nelson Mandela was being elected president. So when the genocide started, none of the top people were around to cover it. But the few of us based in Nairobi went there from the start, so I started my career documenting the Rwandan genocide.

Wow, so you were straight in there with probably the trickiest, most heart-wrenchingly horrific job you will ever experience.

Yes, I remember on one trip sitting on a runway with top photographer James Nachtwey, asking him how he coped with it all. He said: “To be fair, you have really started out on one of the worst ever atrocities, so it’s not easy.” But he did say one thing that has really stuck with me over the years: in order to take good photos you must never lose your humanity for what you’re seeing because that has to be portrayed in your pictures. If you’ve got a wall up to protect yourself, you’re not going to pass that view over properly.

Great advice but what a hard way to work.

You became part of quite a hardcore group of photojournalists seeing some scary moments in history. Can you tell me a bit more about that time in your career?

I’d been on assignment to Somalia [covering the civil war] but I’d been in and out; there was nothing quite like Rwanda, and on an emotional level it was incredibly difficult to handle, witness and try to document. As a professional photographer I didn’t have years of photography behind me. And also living in Kenya back then, we were all shooting film and most of us would shoot for agencies – so it was slides, negatives or black and white, which had to be sent back to our agencies. So every day in Rwanda, one of us would drive to the border with everyone’s packages of film, and pass them across to a pilot flying to Entebbe in Uganda, who would then hand them on to another pilot travelling to Nairobi. My mother then picked up the packages and shipped them. They were sent to Paris, then New York on the Concorde. Those packages travelled more than us! And each shipment cost $400 and that was the 1990s; can you imagine how much money that was for the magazines to pay? The whole process was extraordinary really when you think about digital.

And then you think of the wire services back then, they had their satellite phone, which was genuinely the size of a huge suitcase. It was an amazing time we lived through and I’m quite grateful for that.

With all the film in Rwanda that I shot, I never saw it, so I was never really able to learn from my mistakes or appreciate what I’d done. I only saw all this film for the first time about four years ago. Last year I sat and looked at a few things and it’s the first time I realised I did quite well, considering my inexperience and the fact that there was no scanning, so I couldn’t look back at my work.

Five years after covering the genocide, I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and was off work for a year. It really knocked me sideways and a lot of my colleagues back then all suffered from PTSD.

Opening yourself up to your subject, you can’t help but be affected by such incredible human suffering. I think you’d have to have the thickest skin in the world not to be. The stress and negative impact on mental health is not something easily acknowledged by photojournalists in situations like yours. But it is fairly common; you can’t always stay immune to what you witness, even if it’s your job.

What else has moved you over the years? What are you drawn to?

I’ve found that when I’m really passionate about something I can take good photos. I’ve really got to be moved by it and most of it is social injustice. But it can also be a positive thing out of a negative situation. I’m really drawn to injustice and making the world a better place. It’s what drives me, it’s my passion.

Tell me a bit more about your style, how you work and your vision.

Starting out, I was definitely going more towards showing what was happening in the world. Then with the PTSD, though I do still cover war, it’s usually on the sidelines and showing how it’s impacted. Now I find myself photographing more in a regular social environment, documenting what’s going on. I’m not a news photographer, I’m much better at staying with the subjects and spending quality time, to able to show daily life. I think that’s what I’m good at: showing little moments that will maybe portray an emotion that will draw viewers in and give them a better understanding.

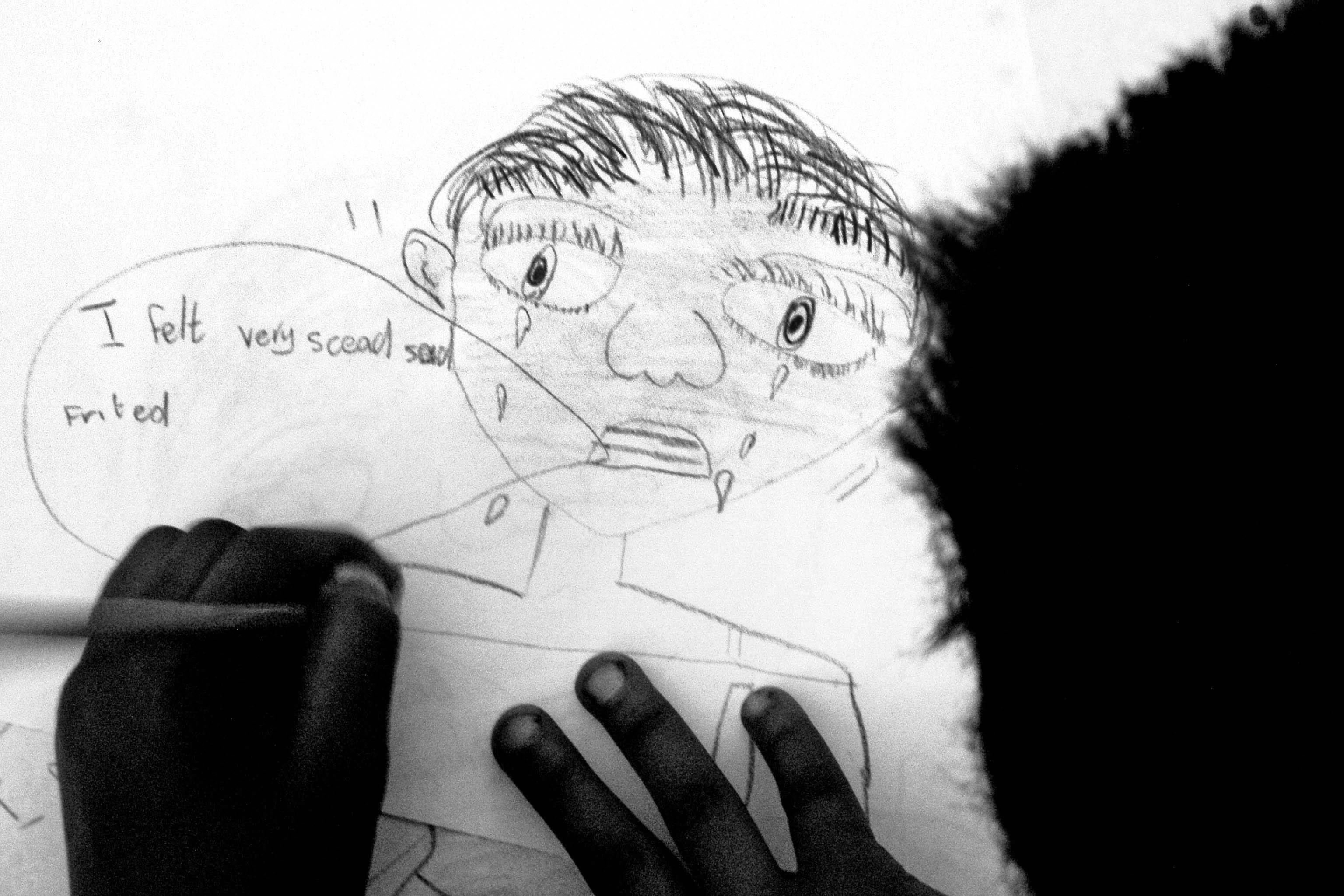

What about your child sexual abuse project, My Piece of Sky? That is has been ongoing for so long. How has it affected your style and vision?

I’ve now spent 12 years doing it, which was not ever something I expected to do. But I sort of got an assignment and the more I researched it, the bigger it became, and the more I felt “I’ve got to get this, I’ve got to get that”. That was very difficult emotionally but also photographically because the children’s identities had to stay hidden.

So I spent more than a decade doing a photographic project where I could not show any faces that would identify the child, which knocked me a bit creatively. I felt it clipped my wings slightly. But I did what I needed to do to tell the story, which is what’s most important.

Now I just feel I want to photograph everything, I feel I’m being drawn much more to the outdoors, to adventure – to breathing a bit more and seeing the beauty of the world. I’ve got to remind myself of this, which was difficult every time I sat down to work on that project.

Can you share a bit more about the project, which has now been published as a book. Reviews have described it as a ‘wrenching, monumental work’ and an unparalleled ‘multi sensorial experience’.

It is a unique body of work because it is the first of its kind to document child sexual abuse in such depth using photography, artwork, journals and interviews.

Child sexual abuse transcends all – it permeates every racial, religious and socio-economic group. I focused my project on South Africa, to show how a country and its people cope with the sexual abuse of children. But this work is relevant globally as it’s a worldwide issue. The book examines how child sexual abuse impacts on the survivors and their families, the effect on child services professionals, police, prosecutors, and the wider community. It also offers an insight into the perpetrators and their own personal history, among other stories.

What an incredibly difficult but vital topic to cover in such depth. You must be very proud.

In my opinion, it’s a really important project and is incredible, not really because of me, but because of all the people who have shared their stories.

You have an amazing talent for getting people in very tough situations to open up to you.

Yeah, I guess I do. I think if anything that is the strength. People do trust me. I also really do everything I can to make sure I never let them down. As a parent myself now, I know it’s not easy if someone came to me with a camera wanting to photograph my child who had reported being raped. It would take an incredible parent to understand and to trust anyone at that point. So I think I’m blessed that people have trust in me and open up to me at really difficult times in their life.

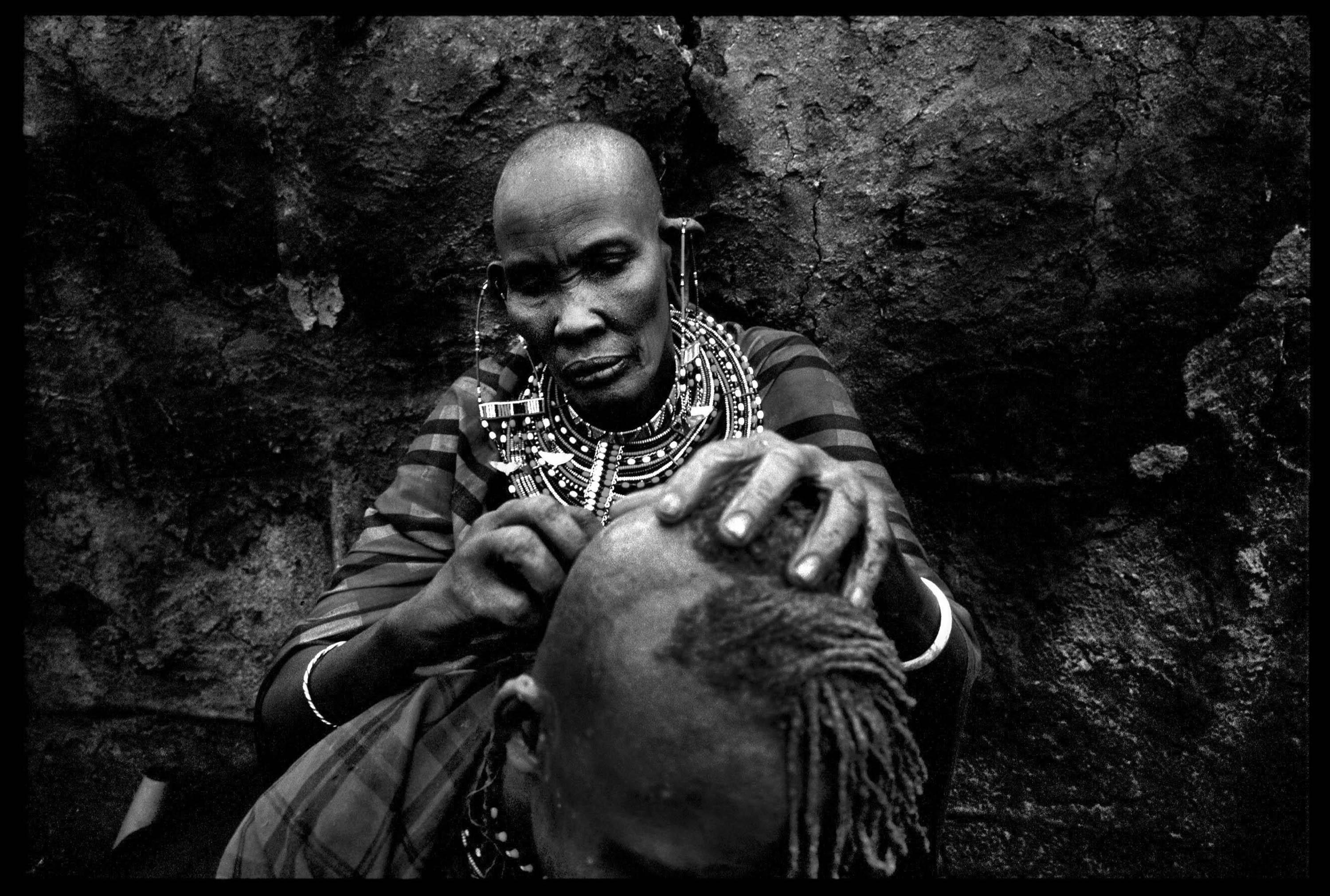

The traditional Eunoto warrior-shaving ceremony looks like another compelling topic to cover, obviously for very different reasons.

It was an extraordinary experience. Traditionally, it’s a time when young warriors get their junior elder status and are allowed to marry and have children. It’s a really important, life-defining ritual that goes on for four days. Their music puts them in a trance, and they sing and dance 24 hours a day, preparing the hut, and then the mother shaves the son’s hair, which has been grown for many years.

What a privilege to witness this coming of age celebration.

I remember feeling very honoured to be allowed to attend this important rite of passage. It was more spectacular than I could have imagined and is a ritual I fear may unfortunately be disappearing with globalisation.

And what about any other memorable or wonderful experiences of life in Africa?

With my hotel management background, when friends once asked if I would help run their safari camp while they were away I jumped at the opportunity. One evening, I was walking out of the well-lit mess tent into darkness to put my dinner tray back in the kitchen and literally bumped into a young male bull elephant that was standing at the entrance. We both had a fright. I, of course, almost had a heart attack. But I can now say that I have seen an elephant ‘jump’. I ended up held hostage by him in the mess area, with him thankfully too large to get in, but just the perfect height to stand glaring at me, stomping his feet and trumpeting for almost an hour before I was rescued. The joys of bush life!

Which photographers have influenced you the most and why?

When I started out I just loved Eugene Richards’ work. [The American documentary photographer and filmmaker] was one of my teachers at ICP and an incredible human being as well as an amazing photographer. Nowadays, there’s a New Zealand photographer, Niki Boon, who I think is absolutely extraordinary. Her work portrays daily life, and it’s beautiful and positive.

There must be people in the world who think you’re extraordinary if you were picked to be on the jury for the World Press Photo Awards in 2015. That’s a huge compliment.

Yeah it was, but it was also one of the years fraught with disagreements. I was very vocal about believing that photojournalism should never be set up. Some people will say as long as you’re telling the story, it doesn’t matter if it’s set up.

For me, if it’s photojournalism, it’s got to be you documenting what you see. The fact that you’re there, and documenting it, is already changing the reality. On top of that, if you’re going to be directing and putting lights here and there, I find that dishonest. On the other hand, if you’re doing something creative to tell a story and that’s honest, then it’s fine, and a lot of great work can come out of that; but not in photojournalism.

We’ve talked already about opening yourself up when you take a picture. Do you consider that the most important thing to remember to get a good image?

Definitely. You need to be open. If you do not allow yourself to feel what is happening there is just absolutely no way you can portray that emotion. But also knowing I wasn’t alone, has been important to remember in tougher times. It was quite a macho environment back then, full of bravado. I think we were all winging it as photographers. But on many occasions I was crying and photographing at the same time as it was all so horrendous. You could just not believe that humanity was capable of this. And there was nothing you could do to stop it.

Wow, I admire your strength in what must have been a very tough environment. On a lighter note, tell me about one of your favourite photos or projects.

One assignment I absolutely loved was for Siemens. It was basically a corporate social responsibility job, which is really what I love doing. The idea was to have an art contest in various schools supported by Siemens around the world, which would illustrate the children’s visions of what an environmentally sustainable city would look like in the future. It was such a positive, exciting experience. And it was great working with a team after spending so much time working alone.

To get a glimpse inside the minds of those children and what they’d like to see must have been such a lovely experience. And I’m told it was a very humbling project as many of them are incredibly grown up for such young people and very aware of the challenges that their cities face. But they also have such a beautiful appreciation for the simple things in life.

I was very moved and humbled by the aspirations and visions these young children had for their future and also their community and country as a whole. They were each extraordinary in their own way, as I think all children are, but we are just so busy with life that we sort of miss it. It was very inspiring.

If you weren’t a photographer, what would you do?

It would have to be either a nurse or something in extreme adventure.

You’ve obviously done that amazing project on nurse shortages in Malawi – is that where the nurse idea comes from?

The project was an assignment for The New York Times. But if I had to reconsider a career, nursing would be one of the things I would do because of an experience with my late boyfriend. He was in a freak accident and was in a coma for six months. So I spent six months with him in hospital. Though it was a very painful time it also gave me such an extraordinary respect for nurses. I actually love hospitals somehow, I love medical stories.

Extreme adventure is about the outdoors and reminding me of the beauty in the world – there is so much out there that I haven’t seen.

You live in such a beautiful country, so pulling yourself out of the intensity of much of your past projects, and reminding yourself of the beauty outside is a way to keep you balanced and happy. Nature is a good tonic, at the end of the day.

That desire to really connect, to tell a story, seems so important in today’s mega-paced world. And your images are so intense and convey such meaning that you really feel transported, as a viewer, to that moment, that story, those feelings.

I think the subject influences the way I photograph, which is quite beautiful as that means they’re kind of giving themselves to the photo and together we’re making this work somehow.

Mariella is represented by Tea & Water Pictures. See more of her work here:

www.teaandwaterpictures.co/artists/photographers/mariella-furrer/