Conversation with Greg Miller

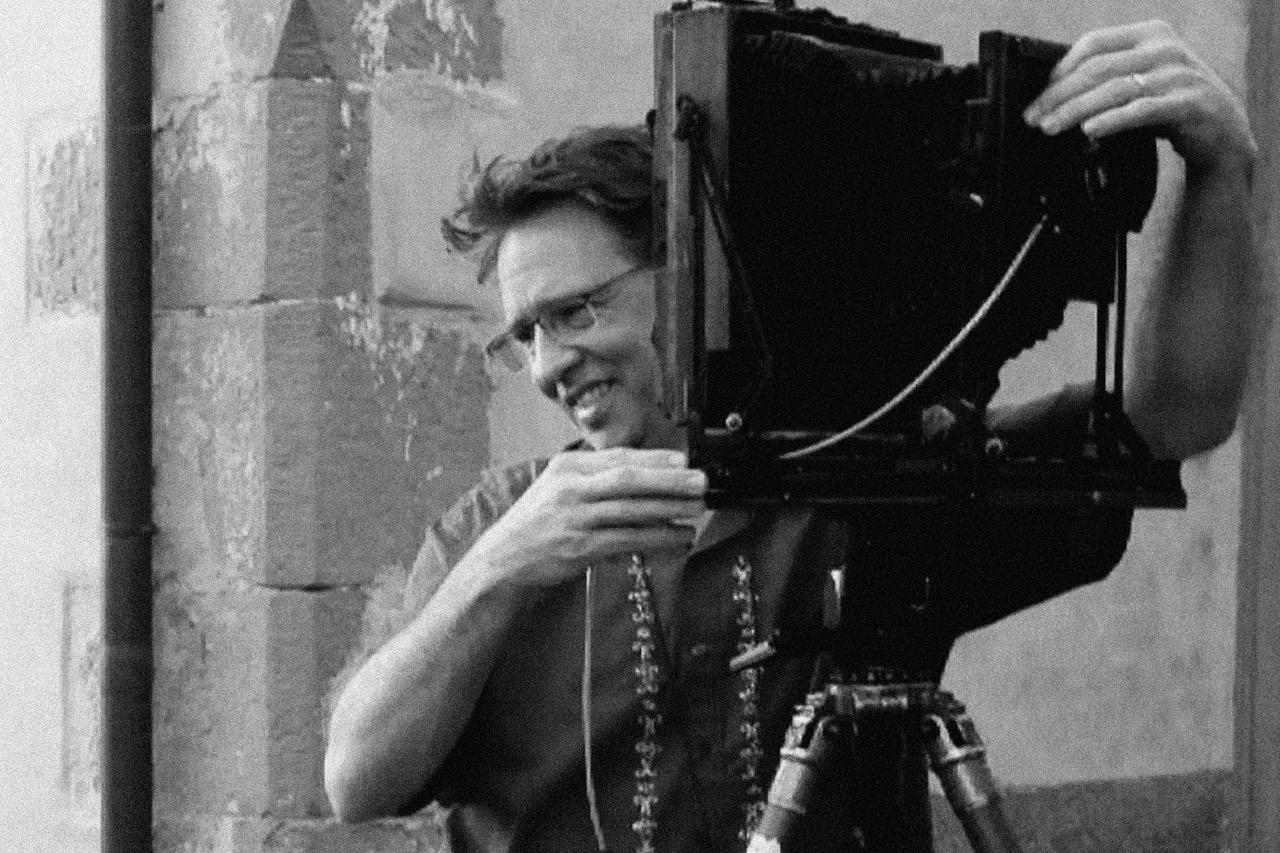

American photographer Greg Miller considers himself more of a fine artist with a commercial career. He uses the serendipity of chance meetings with strangers and large format street photography to build insightful, narrative photographs.

From Nashville to New York and now Connecticut, Greg has moved between small town life and the throngs of city living. He’s always gravitated towards people and began his photographic career more than 20 years ago shooting on the streets of New York. Greg is dedicated to working with an 8x10 view camera whenever he can and uses this to explore humanism through portraiture.

A Guggenheim Fellow, Greg is also a passionate teacher of photography, including at the International Center of Photography.

We chat to Greg about what’s at the heart of being a portrait photographer, his place within an evolving craft and shooting with a large format camera.

He also talks about his experience of collaborating with news organisation NPR to cover a very emotional March For Our Lives demo in Washington DC. Hundreds of thousands of people gathered there to call for stricter gun control laws in the wake of a high school shooting in Florida and Greg was out on the streets documenting it.

As someone who teaches photography as well as practising it for many years, you must have an interesting viewpoint on the craft.

Early on in my career I gravitated towards people. I’ve always been a portraitist. I grew up in a smaller town in Nashville, Tennessee, and then moved to New York for college, a city with 12 million people, so it was a big change. I was attracted to New York for that reason – there are people everywhere. I was also interested in people’s indifference to each other, in the way New Yorkers are.

Over the years I’ve come to realise I’m a humanist and the driving force behind my photography, and also my teaching, is that it’s around approaching strangers and photographing people who are unfamiliar. I think it’s really compelling.

I think at the heart of being a portrait photographer is seeing a beauty in people that they may not see in themselves. Not only do they not see it but the world often doesn’t see it in them. That, to me, is very powerful.

Reminding people of the beauty in themselves and each other seems especially important in today’s world.

Totally. In terms of people, it’s important it’s collaborative. I don’t move in with them but it’s a collaborative moment in making a photograph. That’s important to me – I don’t just want to photograph people without any regard as to who they are. Otherwise it’s not interesting to me.

Obviously the medium of photography and who does it has changed. Anyone can take a picture nowadays. What do you think that means for the future of professional photographers? Do you think those moments – where you can reveal the beauty of someone or something – become more important?

I’ve always felt confident in my ability to make a picture that other people can’t make. If we were to all stand on one spot and make a picture with the same camera it will be uniquely different. Each person obviously has their own way.

Because I shoot with an 8x10 camera, I gravitate to a camera that has a unique way of looking at the world. But I also think it’s about where I put a camera and the way I photograph.

I know there are a lot of photographers dismayed with our current world, with everyone having an iPhone. Certainly the world has changed but it’s actually much like a marketing problem. It’s like standing by the ocean and wishing there were no waves. How I end up surviving as a photographer and being happy making my pictures is what it’s all about. Me as an artist is obviously unique to me and my survival among a million iPhones is another thing.

I’ve always thought the best thing to do, even if you’re at a standstill, is to look within rather than outwards. Think about why you are not getting any work or making any photos – think about what’s right for you and with your photography.

Let’s talk about shooting with this large format camera.

It’s a bit unusual. Commercially it’s like the kiss of death: not because people don’t love the camera, but because it is more intentional and therefore I make fewer pictures. Art directors want lots of variety, of course, and I want to give them what they want. If I’m doing an ad campaign, I work with medium format. The large format has become more for my personal work. And if there’s time with an editorial project, I will use it. When I’m working with an 8x10 it’s like the world comes to a standstill. I have everyone’s undivided attention and that allows me to take liberties with the pictures. If the light is better five feet away, I can pick up the camera and tell everyone to move five feet away. The commercial take away from the 8x10 is that I have become a much better director as a result of working with it.

In the end, I love the camera. I love that it has an optical embrace of people and that’s what I’m interested in.

Part of where Tea & Water Pictures is coming from is that it sees photographers as truly creative people, not just image makers.

I would love for people to be able to see it that way. I think some people think I’m an image maker or might think my projects are made in 10 minutes. But I have a way of working. I’m proud of the fact I’m an artist and come about this as an art form. I like people to have business cards that say poet on it.

You got your BFA in photography in 1990. How did you get into photography?

Most people go to college to study something else and then end up doing photography. But I knew when I was 16 I wanted to be photographer. I was editor of the year book in high school and when I went to college started working for magazines in my second year. So before I graduated I was making money doing this. And I’ve been working commercially ever since.

I had a lot of serendipitous moments looking back: from a really great art teacher in high school to assisting a photographer at that age, too. This photographer had a photo studio across the hall from our family’s apartment and I started working for him. So when I came to New York, I knew a lot by the time I was a freshman. But I was also humble. Even though I look back and realise I was pretty advanced, I didn’t have any attitude.

Tell me about your collaboration with NPR to photograph the March For Our Lives demo in Washington DC, calling for stricter gun control laws [organised and led by students from Parkland in Florida after a fatal shooting at their high school]. It is so powerful, with an intensely emotional audio element, too.

I was really excited to be connected to NPR. This was my first proper assignment for them. Funnily enough, I think NPR had originally thought they would just do photography. I mentioned how great audio [interviews] would be but I think it was actually an afterthought. So they had two interns – a writer and an audio intern – who were there by my side capturing the audio and asking great questions. I loved the collaborative effort on this. We all had our part and it was just brilliant. The photos and audio [available on the NPR site] both speak to the viewer together.

The reason we were there was obviously because of a horrible tragedy, so the day had deeply serious undertones but at the same time it was really amazing to be around a bunch of like-minded people. It was very powerful seeing kids who are out there thinking they want a different world for their future and want their voices heard.

Like children who grew up in the Cold War, we are going to have an entire generation who are raised thinking there is an indifference towards their lives. It obviously has to be fixed because we can’t live this way. And once it is, we will wonder how we were ever in that place.

What a poignant project being out on the streets with these students, their parents and other people, listening to stories and taking pictures.

Moving on to your Morning Bus project, this is a beautiful body of work.

We had moved from New York, where I’d lived for 20 years, to this simple, small town in Connecticut – a milk from the dairy and drive-in movie theatre type of place. A few years after we moved was the Sandy Hook [Elementary School] shooting, not far from us. My daughter was about the same age as the victims. We were all deeply affected.

Living in Connecticut I had already noticed children waiting for the morning bus by themselves. A few months after the shooting I realised I felt a strong connection between their innocence and the vulnerability of the Sandy Hook children. I just felt I had to do this project; I felt empowered. I started with my own daughter in our driveway and then photographed our friends’ kids. It’s about capturing that fragile moment when a child steps outside the door to go to school.

From a parent’s perspective, a whole lifetime of experience happens while they are at school. My child leads a life that begins at the end of our driveway. That spot where the school bus stops is a membrane between home and the rest of the world.

It’s a great concept for a project. That vulnerability is something everyone can relate to, either as parents or in our own memories of being a kid, and those rites of passage that separate you physically and emotionally from your parents.

One project that has a real personal connection for you is Nashville. What does it explore? You’ve described how it meant reconsidering the meaning of home.

I am originally from Nashville. I grew up there but moved away aged 18. After 20 years, I began to think about returning there to explore my home town. But by the time I went back there in 2008, the city had irrevocably changed from the 1978 Nashville I knew. All of my family had since moved (or passed) away.

I devoted several months that year to photographing in Nashville. I would drive around the city, often returning to old haunts, looking around, photographing anything or anyone that even hinted at the past I once knew, as if chasing an emotional divining rod. None of the pictures I made look like the Nashville of my childhood, nor did they really show today’s contemporary Nashville. My pictures are something of a mash-up of the city I remember feeling as a child and the city I found in 2008. What remains is a wandering vision of the place I once called home.

Can we talk about the monograph you’ve worked on, Unto Dust, about Ash Wednesday?

Unto Dust is a book of portraits of workers, business people, tourists and other New Yorkers on the first day of Lent. It started when I was already a street photographer, using this 8x10 camera. I didn’t even know it was Ash Wednesday until I saw people with ashes on their foreheads. I was curious about it. These people were already interesting to me but also just happened to be wearing marks smudged on their foreheads.

It took me a year to realise it could be a project. But I became really interested in capturing the ancient ritual alongside contemporary New York life. I’ve photographed approximately 300 people over the years.

I’ve been working on it for 20 years. But it’s obviously only celebrated one day a year so it’s really only 20 days of work. But I do photograph intensely each time. The project is a kind of humanistic meditation on Ash Wednesday. I’m not catholic but I’m interested in people’s relationship to their religion (as I am interested in my own). I’ve learnt so much about the complex practice of faith and portraiture.

The book will be about 50 pictures, full bleed, one after another with no captions. It’s due to be published in September. I’m really excited about it.

See more of Greg’s work here

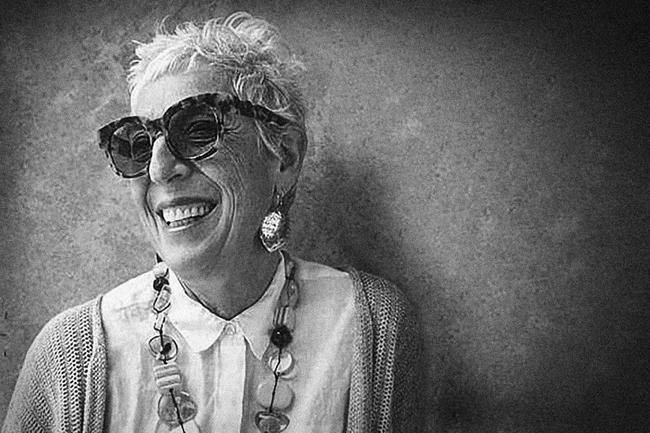

(Header image photo credit: Elisa Mercadante)