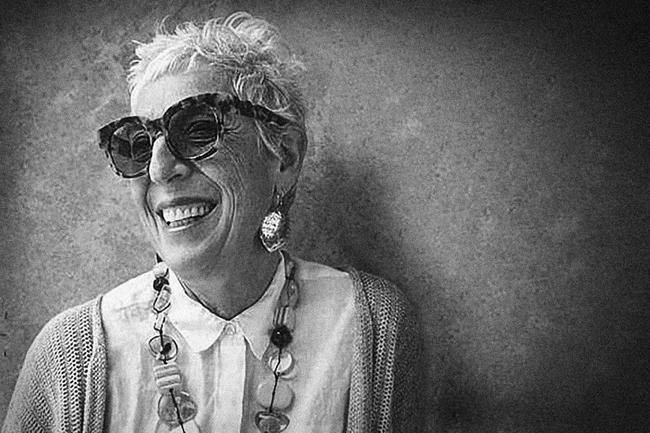

Conversation with Emma Cousin

Emma Cousin is a painter living in south east London with her husband in their very empty house. She is an artist first and foremost but also a poet and curator. Her art has a lot of wit and heart and a beautiful boldness.

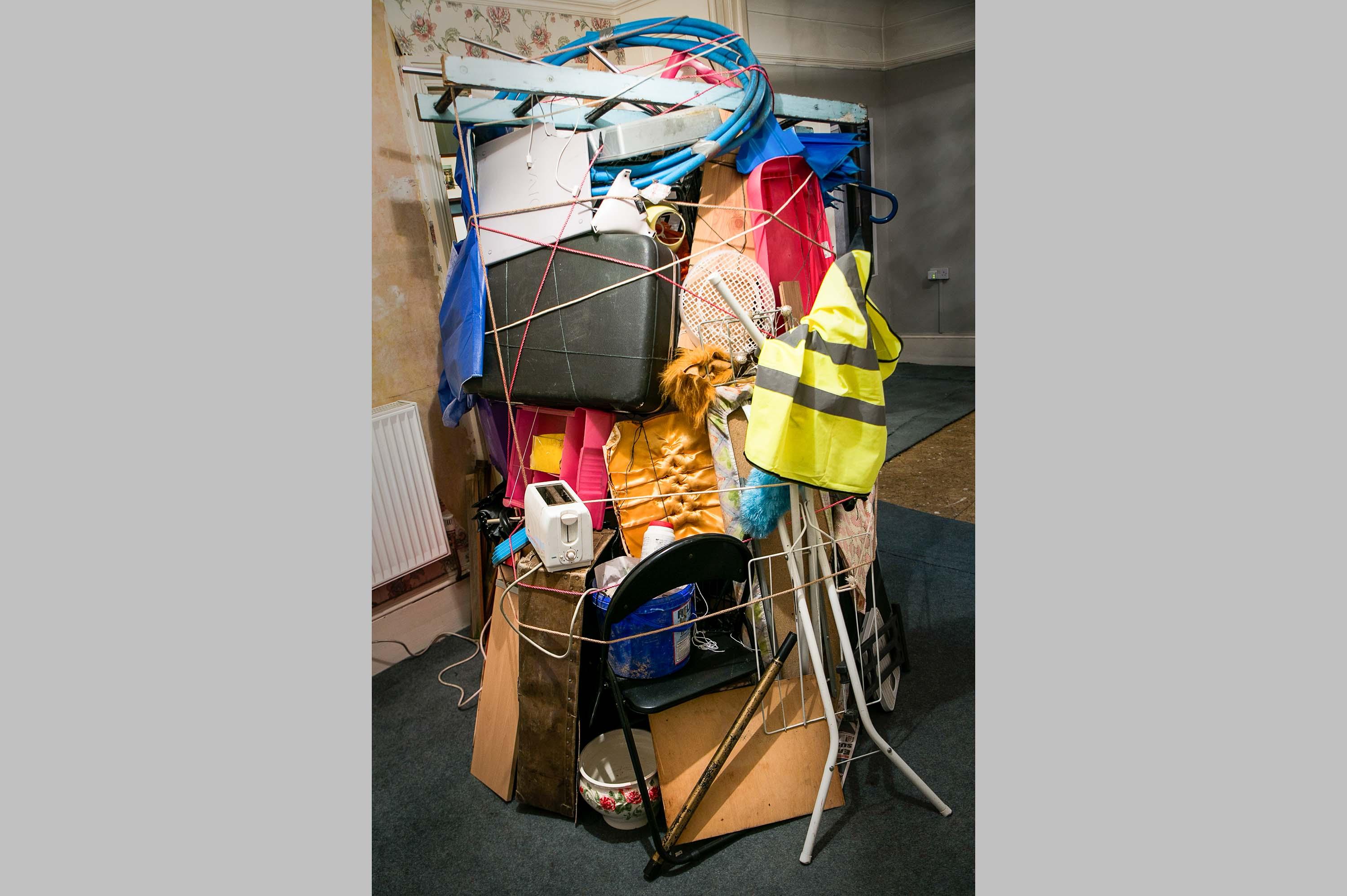

Emma is also part of the brains behind artistic venture Bread & Jam, a unique series of exhibitions created and exhibited in the pair’s gutted and soon to be refurbished Victorian house in Brockley. She and her husband emptied and opened up their home to invite artists to bring their ‘ingredients’ to the property and make something new; to start a conversation in their work, between rooms and other artists, and the viewer. The exhibitions also push what they can make and create in response to the house, challenge and question what role a gallery has and how art can and should be experienced.

We interview Emma at her studio in Deptford, in a building shared with everyone from fellow painters and sculptors to storytellers and an art psychologist. There’s a rolled up yoga mat perched in the corner, which doubles up as a bed now and then when she can’t pull herself away from her paints.

I’ve seen your style unfold in recent years and would say it’s cheeky, smart and vivid. How would you describe your art in three words?

I think ‘funny’ would be my go to, also slightly surreal, but I’d fight that a bit as I think it’s quite real, so ‘real-surreal’, and hopefully ‘painterly’, as I want it to be about paint as much as anything else.

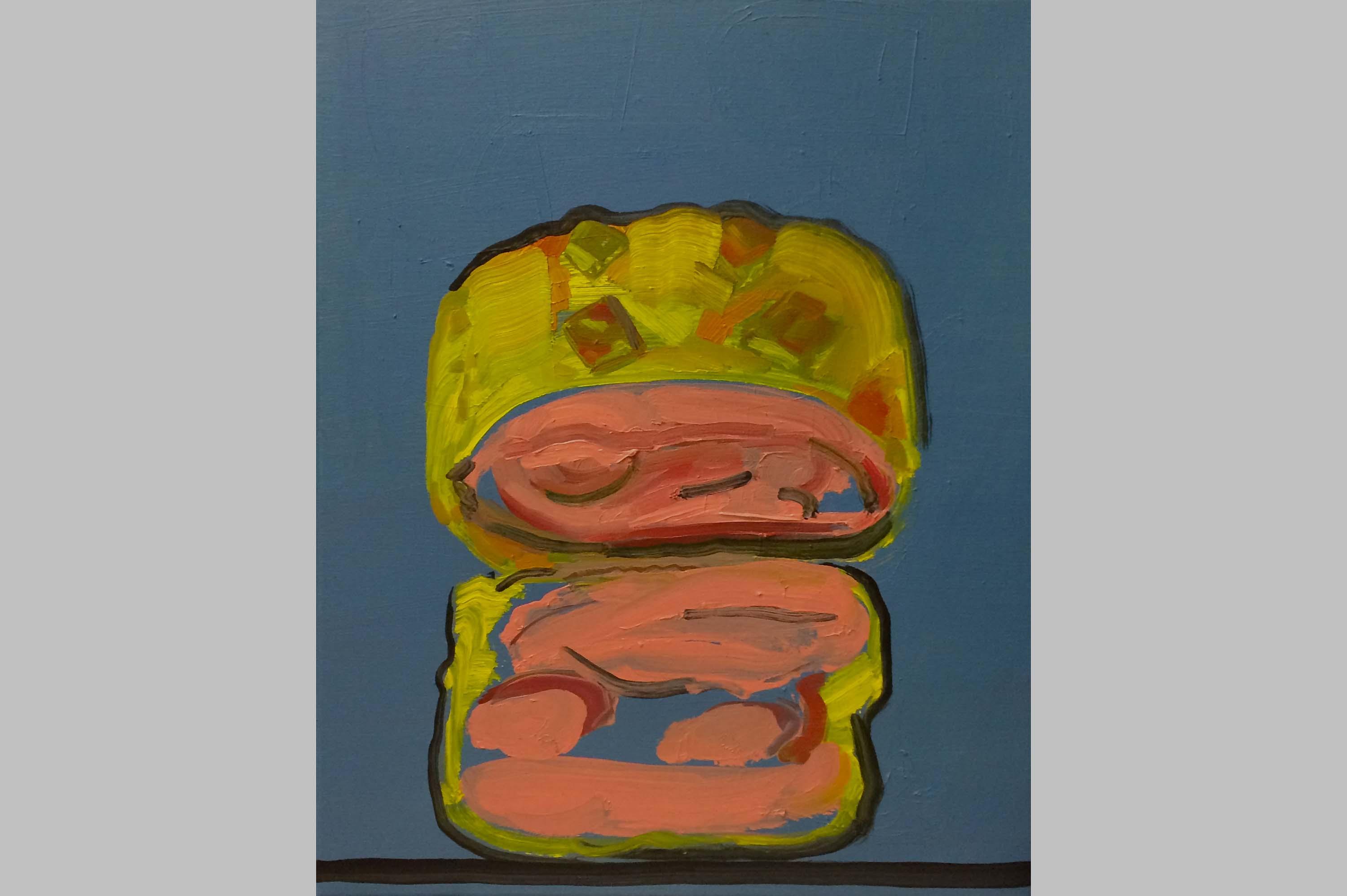

‘Self portrait as a piece of ham - Emma Cousin’

Tell me a bit more about your style, the challenges, and how you feel things are evolving for you.

It feels a lot more focused. The problem for artists who are representational is often that you have loads of ideas and it’s all imagistic; so it’s almost like visual Tourette’s. You have these images that come to you, a bit like a poet would describe words coming to them and this automatic writing, so it’s like an external voice. Images arrive and boom, that’s it you’re painting. But often what you’re left with is an illustration of the idea you thought you’d had, which is not the same at all. So it’s about how to capture that sort of intangible in-between space of something figurative but something you recognise and something which catches you out as a viewer and a maker. I want to make something that surprises me.

There’s a real discipline to dissolve it [an idea] down, let it simmer, make more sketches, or even write about it, read about it, think about the concepts behind it and drive behind it, and make the painting. Urgency is important for spontaneity but not necessarily helpful to actually distil the ideas. So, for me, it’s becoming more important to read about it and think about it. And I’m also being more disciplined about making a drawing. Even if I’m just sketching or annotating, I’m more careful with myself and fastidious about the detail.

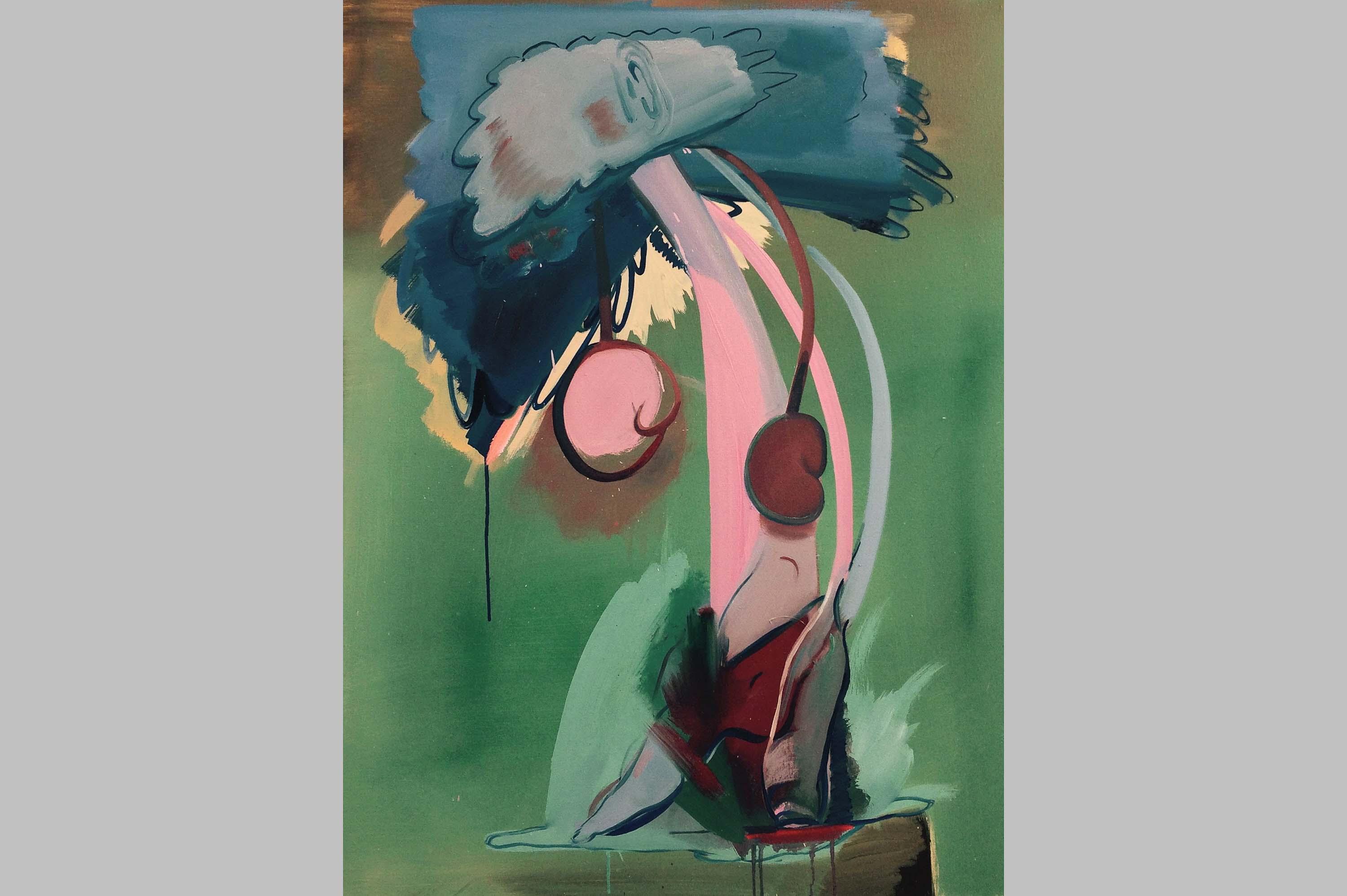

‘I wanted to be a ballerina but it was too painful - Emma Cousin’

You must find it quite tricky to switch off, given the subject matters I know feed your imagination – such as the body, decay, death, and perishables like food, our relationship with food, and our relationship to our bodies and what we do to ourselves.

Yes, I have found that; it can be overwhelming and once I start reading more philosophy, that opens even more doors, and I’ve also been writing a lot more, writing poetry and short stories, so that opens yet more doors. But the writing really helps me to formulate my ideas with clarity.

And what inspires you?

The banal, everyday stuff, everything around me – people and places seem to inspire me. If it plays back [in my head] then I know there’s something there. It’s important to be in the right headspace even when not in the studio, because then you start to notice signs and things right in front of you because you’re open and you’re enjoying the ride.

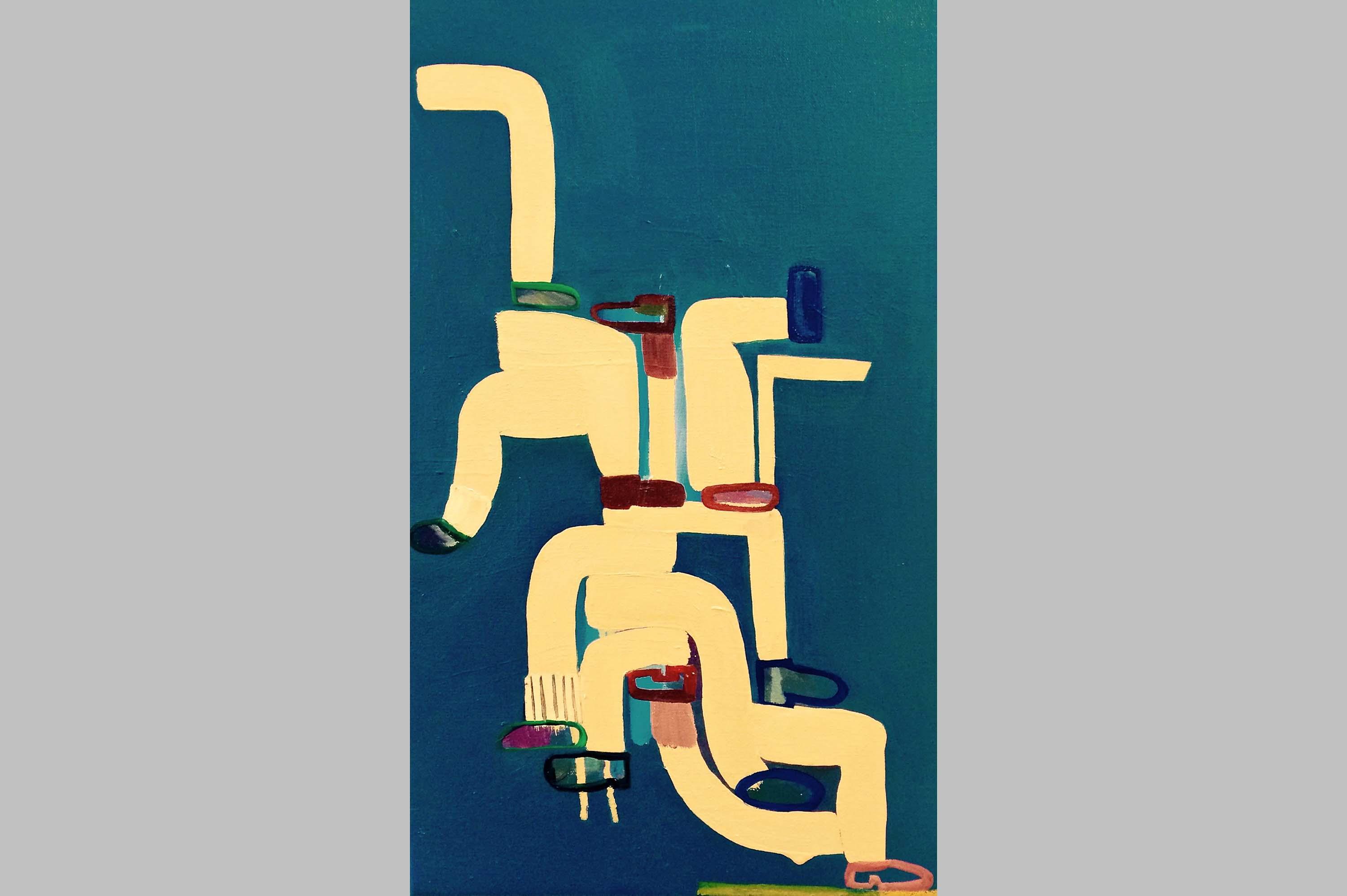

‘Vacuous couple - Emma Cousin’

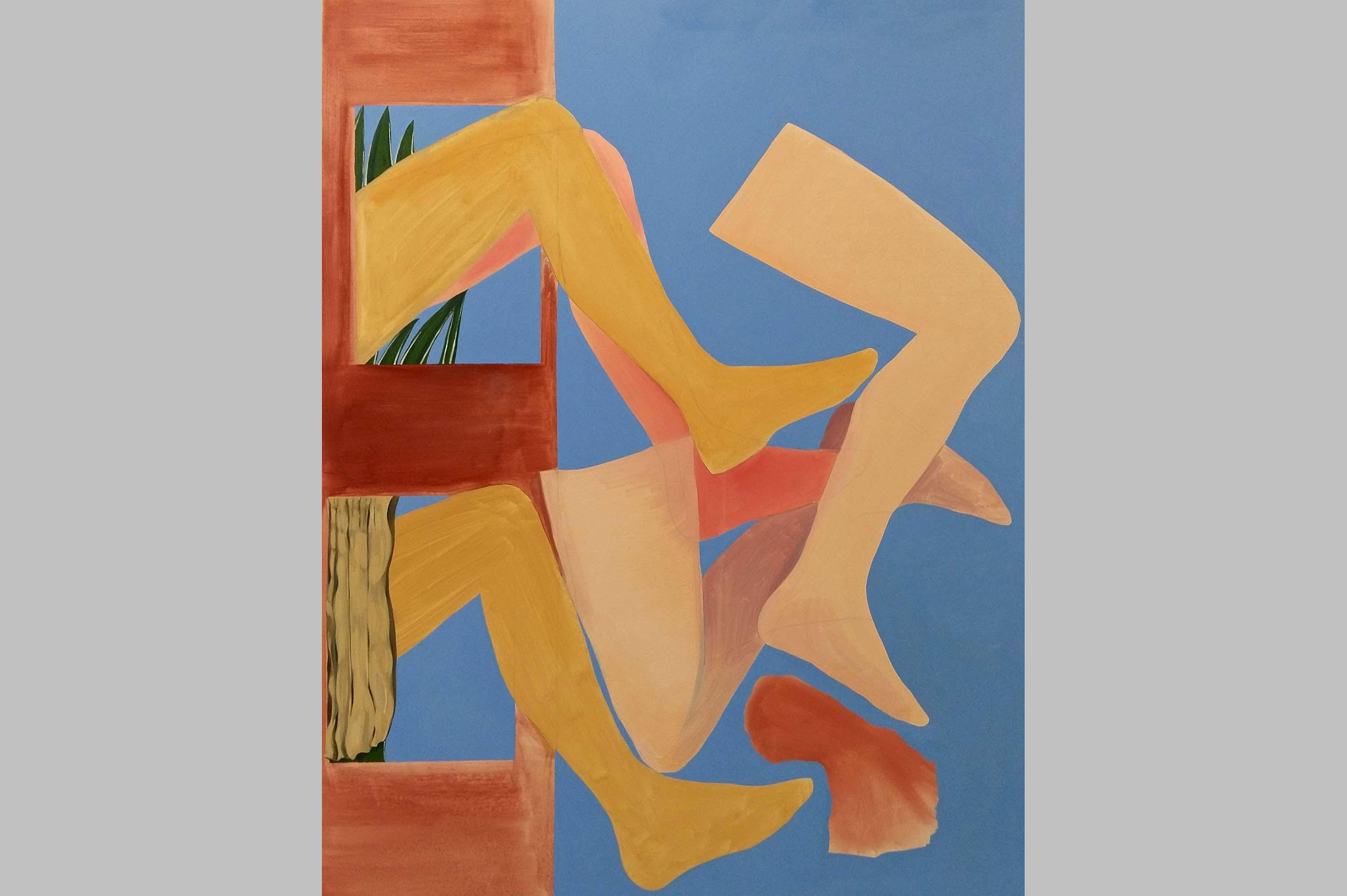

Your most recent body of work, The Leg series, has literally got ‘legs’; it’s really developing beautifully over time. Talk me through it.

It’s based on the symbol of the leg; so it’s about painting a leg over and over again as a motif and what that becomes. You can recognise what a leg is visually; anyone can have that stored in their consciousness, even a three year old…So you have a certain visual vocabulary, which I’m also interested in, in terms of language and how we communicate. Then you can do things to subvert the leg so it becomes more to do with decoration, pattern, building, falling, implosion and it then becomes about forms and shape; it represents something we recognise but in a very different reading. So it’s a way of using something figurative but actually moving beyond that.

There’s also something in there about the accumulation and about volume – a reflection on that and what that all means and how we all fit into each other.

It’s become a really interesting investigation. And it really started by just playing with the leg and how it fitted with other legs. I started thinking about collections of legs and what could happen next and how to fill in the gaps between the legs. So I was thinking about play and about Hula Hoops on fingers, eating them off your fingers, then the balance between waste and keeping yourself fit and young, then images of holidays, balls, beach balls, juggling and circles. So it all then had this whole other wonderful vocabulary. I then got the sketches down on paper and there was enough there to work with and it’s really developed from there.

‘Leg up - Emma Cousin’

‘Throwing in the towel - Emma Cousin’

‘Collision - Emma Cousin’

How has painting influenced the rest of your life?

It really informs the way you look, the way you see, particularly colour, patterns and light. I can walk down the street at night and see this searing orange leaf on a Prussian blue sky, with a black tree because of way the light is shining and it’s a celebration of why we’re alive.

When I’ve talked to you about an existential angst that drives everything [for me], it’s not a negative thing; it’s more of a cerebral thing – not in a morbid way – but it makes things funny. Even in the most catastrophic situation, I often find myself laughing out loud and more and more I’ve let myself go to that. I saw a little girl in the street once, who had bumped her head badly and was really screaming, being dragged by the hand by her mother and told to be quiet. And I thought why shouldn’t she scream? How great if we all did that and just let go a bit more. You go to India, for instance, and there are horns going off every five seconds, combine harvesters are bobbing along playing amazing tunes, because it’s their way of celebrating life.

With a lot of jobs you can separate yourself from your career – it doesn’t necessarily define you. But I think it defines you as an artist. You can’t separate the two. How do you feel?

I wouldn’t define it like that. It’s something you are driven to do. In spite of money, wealth, reward, acclaim and so on - though I’m not saying these elements don’t factor or impact. What I love about it is the sense of play; nothing is off limits. Say I’m looking at what a peg does; I remember a really early conversation with an artist (I was making peg paintings) and he said what’s to stop you getting naked, putting pegs on your nipples and dancing around the studio to feel what pegs really feel like. And I was like “Oh god, I can’t do that” but actually it’s important to let go. For example, really think about the life and death of a banana as a character. Perhaps you need to sit like Robinson Crusoe watching a banana for a whole day. When does it bruise? How do those bruises form - is it the same as the human body? All these things, you wonder, are they mad? But then you have to ask what’s valuable about madness? What’s salvageable? Maybe there’s something really good about that madness.

Moving onto Bread & Jam, what’s it all about?

The main aim is to give artists the time and space to make new and exciting work in an environment which is free and free from constraints. When we invite artists, the first thing we do is have a brunch, with bread, and everyone brings something - jam, apples from their trees, tapas. We walk around the house with our tea, bread and jam or whatever and share a conversation, so it all begins from there. It’s a much nicer way of getting a conversation going.

The idea is to take your ‘ingredients’ or essentials as a person, as an artist, as a maker, and bring them together to extend the conversation and take you somewhere else. The idea of a loaf of bread being shared at any time of day has a really nice resonance about memories. If you asked someone when they had their first baguette, mine was in a field with my little brother. On holiday, there is a certain idea of luxury for breakfast, there are all these jams, with foreign names on them, and then there is the homemade element; everyone is baking their own bread these days. And the artists themselves often bring things – homemade jam, or weird things that can be served at the same time. We’ve had banana bread from a Jamaican lady. It’s generosity. It’s people thinking “I want to get involved somehow”. The nice thing is that people are now offering up spaces from Camberwell and Camden to Penzance [so that Bread & Jam can continue] as they’re aware it’s going to finish and they love the concept.

‘Its so continental - Biscotti (Emma Cousin and Jack Sutherland)’

What a great thing to come out of that; individuals wanting to help each other, to collaborate.

Yeah, it’s fab. And it all started simply as a conversation with two other people. I run it with Rebecca Glover, a filmmaker, and Emily Austin, who is essentially a curator but runs a gallery. I didn’t know either of them that well I just mentioned the idea to Emily over coffee. She said she’d do whatever I wanted to make it happen and suggested a meeting with Rebecca, who might want to help. Then we made a list, went away, and there was a massive period wondering if it was going to happen and how. And it just did and we all did our little bits and it worked really well and it’s exciting that we’ve each brought a different energy and interest to the shows.

‘Universal futurological question mark - Julius Koller’

So it started as a conversation between you three, then with the actual art and environment of your house and what the rooms look like and then it becomes a conversation with the viewers.

Often an artist will be there invigilating, so the public can ask some probing questions. And because it’s happening in a house and in this state, and because people have a cup of tea in hands, people are quite genuine about asking direct questions that they probably never would do in a gallery space.

I think a lot of people who go into a traditional gallery space slightly shrink into themselves; they can be desperately trying to understand a piece of art without asking any questions.

Whereas in Bread & Jam they feel more qualified to challenge it, which is great. It should be a forum for discussion and debate. One of the shows we’ve had was videos – screenings of mini videos never seen, either because they weren’t allowed at the time because they were from places under dictatorships or oppressive environments, things that were lost or went into private collections or things that are sort of art and are videos that people have made.

‘Tower - Marcus Orlando’

‘Untitled gold shoe. 1966 - Yayoi Kusama’

What about compiling a book to showcase the journey of Bread & Jam and condense the best bits?

It would be great to make a book. As a phenomenon, Bread & Jam is a testament to the goodness in humankind and the thirst for creativity, and curiosity, and how vibrant, how alive that is. From the seven year old who lives around the corner, and has been to every single show and sits in the corner, watching the performances twice because she’s so excited about it, to the neighbours who come with kids and babies, and to the woman who used to live in the house.

‘Shard work with Ernesto Molina - Louise Ashcroft’

The weirdest thing that’s come out of it is people’s judgement of us [as a couple], because it’s our house and we live in one of the rooms. How that implicates what you’re sacrificing or your values in life. But although it’s challenging to eat your tea around a huge inflatable sculpture that makes loads of noises, it’s actually brilliant. If you’ve had a really hard day at work and you come home, to sit there in that context is hilarious and ridiculous, but, I would say, an ultimate privilege.

‘Modern Mirror - Justin Hibbs’

Bread & Jam V, the final show, opens on 27 May at 52 Whitbread Road, Brockley. It will feature works by more than 15 artists and include practical lessons on how to snare a rabbit plus a live beat box party performance.

breadandjamwhitbread.wordpress.com