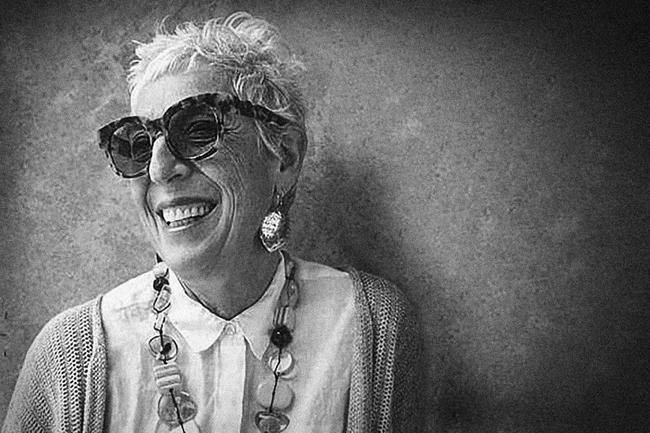

Conversation with Christopher LaMarca

‘Raw’ and ‘visceral’ is how American photographer Christopher LaMarca describes his work. He is all about being emotionally accurate and truly getting under the skin of a subject over time. Moving the hairs on people’s arms and making them feel something is far more essential to him than trying to influence their beliefs, though most of his projects are bound up in thought provoking environmental and social justice issues. These include his career-launching Forest Defenders project, where Christopher documented eco activists over five years fighting to save some of America’s last wildlands from logging. His images always burst with an intimate, honest beauty and when talking to him you can’t help but be moved by his sincerity and spirit, and the importance he places on true long-form storytelling. At the end of each long project he says he feels so astonished by his life experience and what he was just privy to, and how differently it makes him see the world; an attitude some of us could probably do with a dose of now and then. Christopher, who lives in Portland, Oregon, is also a director and cinematographer whose two debut documentary films examining vulnerable and hard to reach subjects have gone down a storm.

How would you describe your style and vision?

I think my relationship with photography and filmmaking is more in line with a traditional painter (though I did not get that gift) than a filmmaker, because compositionally I’m more attracted to less, than more – stripping away rather than adding.

That sort of answers my next question. Apart from making a living, what motivates you to keep taking pictures – intellectually, emotionally or say politically?

If there are just one or two words that come to mind with my work, it would be ‘raw’ and ‘visceral’. Because of where this world is heading, I think that every day, people are moving more and more away from a daily visceral action in anything in their lives – whether their own lover, child or work, because of our relationship to screens; how we interact with each other. This is not breaking news, of course.

You’ve got to hold onto what you feel is going to make people truly connect, to sit up, and feel alive, because, as you say, we are all so over-connected to technology now.

The way that stories are being told is also really, really important, especially with regards to this current media environment, where everything is a 24-hour news cycle of a lot of bullshit. And I think the art form and the connection through long-form storytelling; being able to really spend time with people and tell stories over the course of time, and not have to rush them in a vacuum, due to the current market or system, is so important.

But it’s hard right now, especially to make a living wanting to tell stories in this type of way. As a photographer and filmmaker I want to really get under the skin, and not make things more pre-presentative, just for the sake of it. To make people feel something – that takes time. And that, to me, is the most important thing.

There’s also this internal meter I have and the minute it feels in these situations that I’m taking something from someone; you know “I need this; I have to tell this story” – that’s a horrid feeling to have. There’s an extreme amount of vulnerability on the other side of the camera for people to open up to me, and that’s when I remind myself that I need to be a human first, and the work comes second.

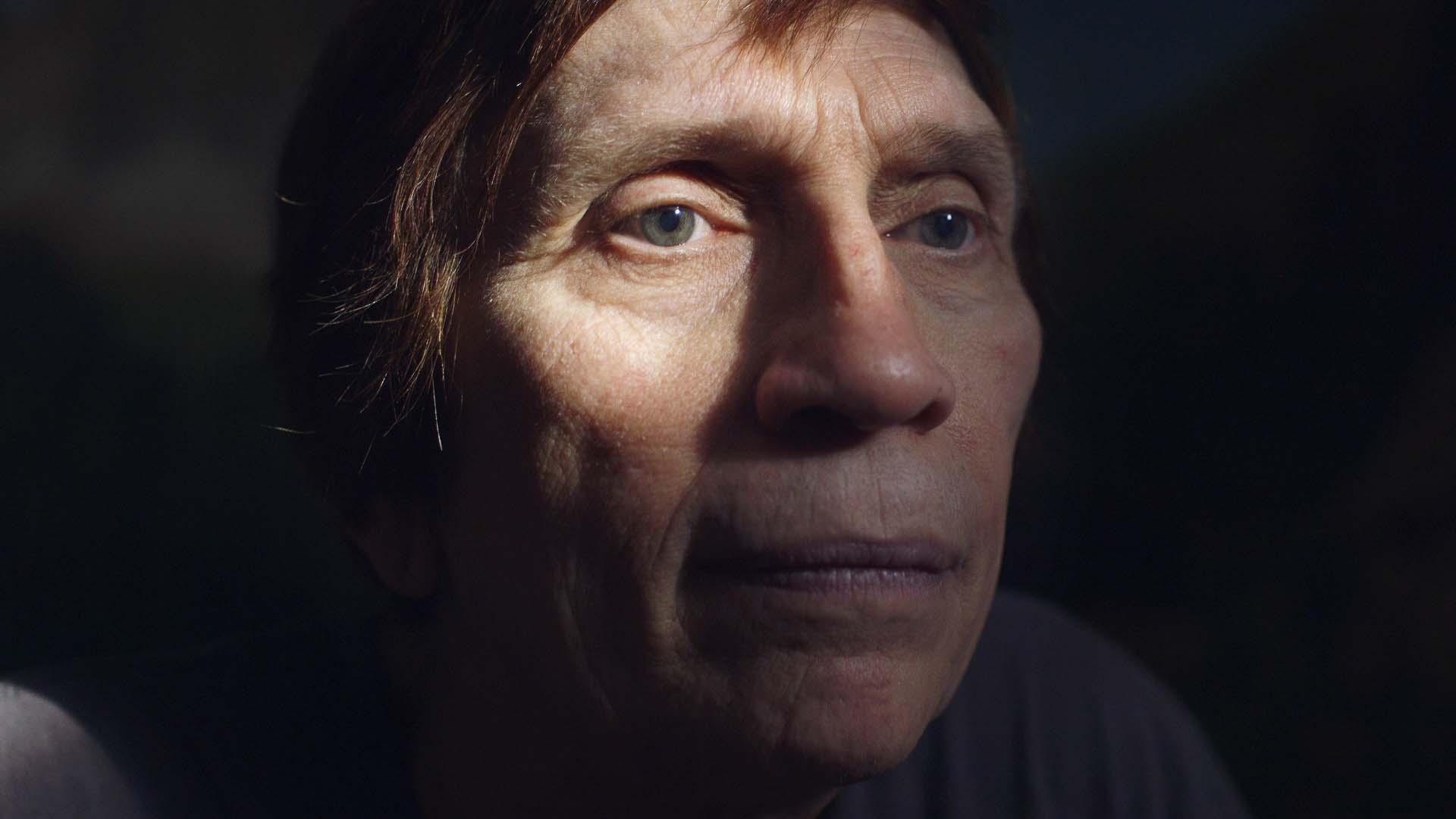

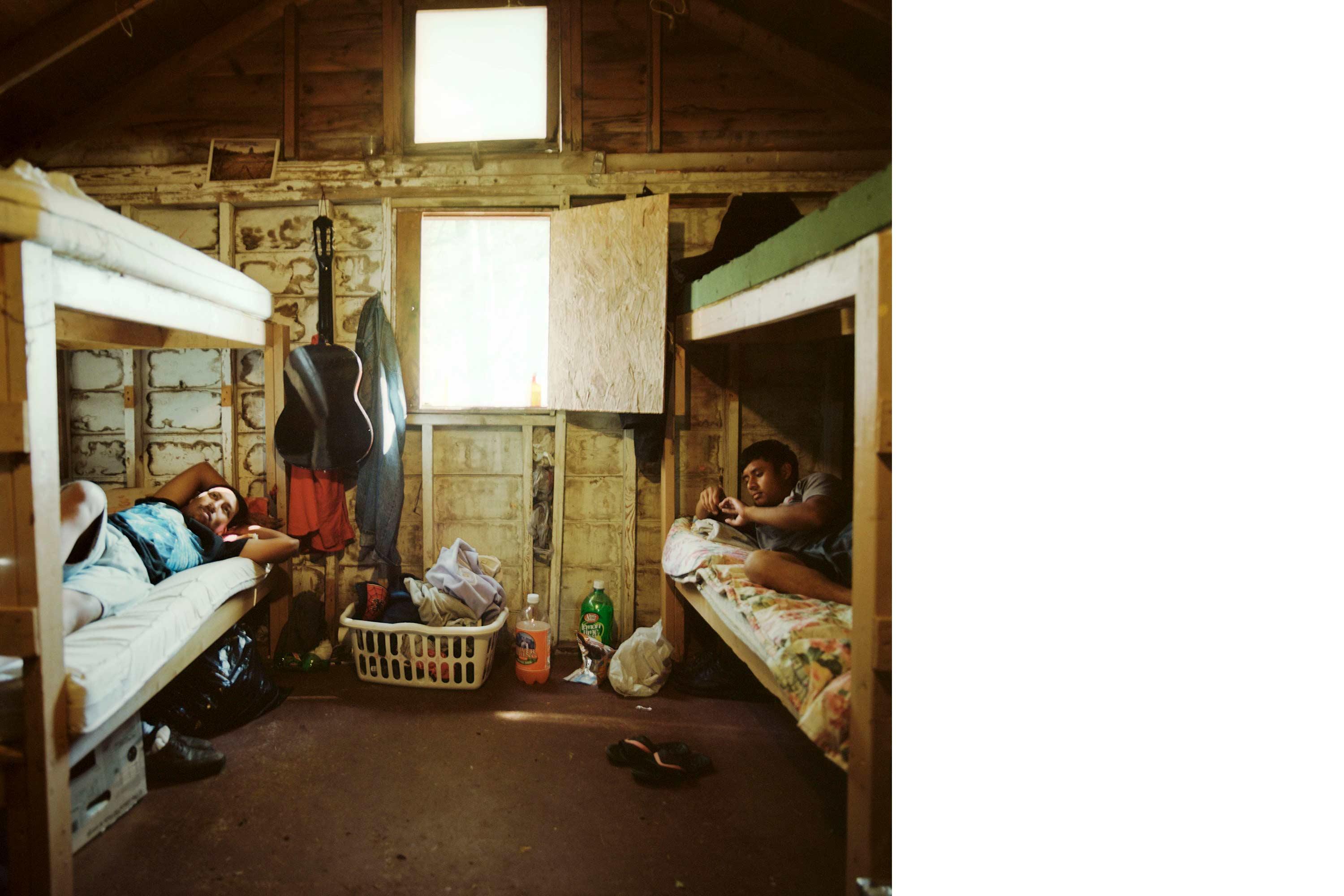

These sentiments really sum up your most recent personal projects and directorial debuts, the amazingly well received documentary films Boone and The Pearl. For Boone, you lived on a goat farm for two years and for The Pearl, you and co-director Jessica Dimmock followed four transgender women for three years.

Yes, with Boone, it’s three isolated farmers living in the middle of nowhere. You don’t just show up with your camera. It’s a very push and pull thing; it’s like courting. And for The Pearl, we were asking that people who have been hiding their true selves open up to us in the most pivotal moment of their entire lives. This was a very slow and gradual opening of trust on both sides; it took an entire year just to gain initial access. We filmed for three years, with our goal being to bring viewers into the emotional realm of these older women as they collectively and individually went through transition.

What did you gain from these experiences, aside from the documentaries themselves?

The best thing I’ve taken from the Boone experience is the resilience I have and the hours I’m able to work or be out in really bad weather conditions. You understand what it takes to live that way, to really be outside and keep going no matter what. I was pushed way beyond my boundaries making that film. And that I have forever; it’s engrained in me now, burned into my chest. And that feels like a huge gift. While making The Pearl I would constantly ask myself “If I was in the same position as the women in my film could I be as strong and resilient?” “Would I risk everything in my life to reveal my truth, regardless of whether I lost everything and everyone closest to me?” Making The Pearl re-defined my relationship to the meaning of the word strength and the practice of self-love.

I mark my own life by these projects [photography and film], because they’ve all been multi-year projects, and at the end of each I’ve been so blown out of the water by my life experience and can’t believe what I just witnessed, what I was privy to and what a gift, and how differently I see the world.

Back to photography, your bio makes for impressive reading. It includes being one of the top 30 emerging photographers a while back for American trade mag PDN for your Forest Defenders project. You were also a winner in the annual American Photography competition for your images capturing some of the aftermath of the 2011 Mississippi River flood. This saw you canoe 300 miles from Memphis to Vicksburg to assess the flood damage. How was that?

That was so crazy. I almost felt like I was going to die on that trip, to be honest. I had slight hypothermia. I was living on the Boone farm then when I took that job. To this day, it’s probably one of the best assignments I’ve had. Going into it – it had never been done before. This was the first time the river was wild and in its natural state and wow, what an opportunity. Rivers aren’t like this any more really. I was in the right place [mentally] to take the job – living out in the elements [doing Boone] and feeling very strong and confident in myself that I’d be able to do something like that. But it was just amazing. The police and army core engineers kicked everyone off the river because houses and cars were literally floating away. It was very post-apocalyptic. It was beautiful; we were floating through what would normally be neighbourhoods, with abandoned houses with water up to their attics. Here we were with no sounds at all, just on this canoe, and we felt like we were on another planet. It was really exciting.

Tell me a bit about your background and how you got where you are?

I got here very much unplanned. I didn’t come from an art background. There are no artists in my family; I wasn’t raised like that. I was raised in a big Italian American family in New York. But my parents were also New York City school teachers so they were very liberal and open and have been completely supportive of my path. But I think that everyone around me was completely surprised by what I started doing because I never took a photography or film class in college. I studied environmental science and biology and fell in love with the outdoors. And I found photography while travelling through West Africa over the course of six months while studying folklore, drumming and dancing, which was another big passion of mine.

What do you feel you’re known for with your photography? Why do people pick up the phone and want you on a job?

I think people know the images I take and gravitate towards are very ‘close’; I gravitate very close to people, that’s where I feel comfortable and that’s where I like to portrait things: energetic experiences of people and shooting on fixed lenses. Always what’s going on in my mind, and I think people know this when they hire me, is “What would it be like if the person looking at this picture was here? What would it feel like to be here?” I’m much more interested in what things feel like than what they look like or what I’m trying to tell you.

Also, most of my work has to do with the environment in some way or another. The first body of work that really brought me out of the woodwork and put me on the map was my Forest Defenders. So once that work came out and I was starting to show it around New York, people were really taken by it and since then, environmental and social justice issues have been threads throughout my career.

Tell me a bit more about Forest Defenders, which I know was also published as a monograph by powerHouse Books.

To this day, the biggest lesson I learned while shooting Forest Defenders was the power of a tight-knit community and the bond that is created around civil disobedience; the feeling of defending something you love, no matter the consequences. I think most people forgot that this country [America] was founded on civil disobedience; a very important part and reflection of a true democratic society. Everyday people are the only ones who can ever really create change in this world, not politicians.

You’ve done so many other amazing projects, it almost feels wrong to single any out. But your images of the isolated Waorani people, which took you to the Amazonian rainforest, look especially fascinating. Can you tell me a bit about their culture and environment, what they were like and why you were there?

What makes the Waorani project special is that their traditional homeland is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also sitting on a huge oil field that is/will be exploited by the Ecuadorian government. This tribe has a history of being able to keep outsiders out of its land, often through force, but this recent discovery of oil will probably end up destroying its culture when history is said and done. As people, they are hunter gatherers who have always been self-sufficient and able to live off the land and fend for themselves. They live in the rainforest and are very wary of any outsiders. They are stern but warm and full of laughter.

Are you still doing what you love?

That’s the whole thing about it that’s awesome. First and foremost, all the work I do in my photos and film, none of it is because I’m interested in an issue and I want to raise awareness about it. I actually think that approach is counter to what people want; I think that setting out with a set of specific rules and ideas that you want to get across is the wrong way to go in today’s world. Hearts and emotions change minds; statistics don’t. People don’t want to be told anything any more and I think the greatest teacher for that is empathy, and regardless of whether someone is a Republican or Democrat, rich or poor, when people feel something, genuinely feel it, and without an agenda, that’s how you move people. And that’s how you bring about change, openness and can bridge gaps between people who normally wouldn’t find themselves together in the same room. That’s what I’ve learnt over my career 100 per cent.

We’ve touched on what motivates you to keep taking pictures. What’s the most important thing to remember to get a good image, in your mind?

There’s no one set rule; it depends on the person. There are two extremes. Sometimes it can be as easy as chatting someone up before you shoot with them – getting to know them, finding common ground to help loosen them up. But if you try and get too vulnerable, too quickly, then they can put up a wall immediately. So I think it really just depends on the people. It’s about listening and not speaking first. And through that it’s about gauging a person’s comfort boundaries. Really sitting and genuinely ‘being’ with that person will lead you to the next steps, and making an image that’s beautiful, that really feels emotionally accurate in that moment. And I think if you do that, even if the image isn’t considered flattering in today’s world, the other person will look at that picture and say, “You know what, that’s an honest image of me and I’m proud of that”.

Can you remember the first photo you ever took?

I actually can and it’s kind of embarrassing. It was on a winter morning when I was living in New York. I think I was in high school and my father was on a sabbatical at the time, and had taken a local photography course. The camera was lying around and I saw this beautiful red cardinal land on a tree covered in snow. I had this almost bolt of clarity of just understanding colour, composition and timing, all in this one moment when I was not looking for it. And I took a picture of this cardinal. It was too far away but the point was that in that moment I fully understood what it takes and what it’s like to be present with the camera and what that instinctual response is.

I don’t think that’s embarrassing; it’s beautiful. Even if you feel the picture was cheesy, the point was what it made you see, how it made you feel.

Exactly – having a response to a moment that might not happen again and it moves you in a way that makes you want to live longer – that’s the best thing about a camera. It allows me to engage in a moment on a level that I can’t necessarily reach without the camera; it drops me into the moment that much more, it allows me feel that much more present.

I hear you like to shoot with a Hasselblad.

I fell in love with the Hasselblad early on. I love the format of it, the way it feels – the whole physical experience of the camera. I don’t like having a camera in front of my face; I like to shoot from the hip. It feels more of an extension of me.

If you weren’t a photographer or filmmaker what else would you do?

I think I would do some kind of esoteric science job – like a fire ecologist. I’m fascinated by [wildland] fires and forests and how they affect wildlife. I just love how it’s all working elementally; it’s something that happens over the course of thousands of years and we try and understand that in our puny little lives. I also have this really strange interest in designing window displays – the mannequins, the rooms; setting a stage basically. I love that. And I love the fact that there is a built in audience of random people who just walk by. It’s almost a form of guerrilla filmmaking, in a way. No one pays; it’s just there. No one necessarily even gives a shit – you can choose to look at it or not.

How do you think you’ve evolved as a photographer since you started out?

Things have become more refined in my approach. I listen to my instincts quicker and I’m able to get out of a cerebral place and into an instinctual place faster.

What about the future for you?

Coming out of six years [of documentary work], I want to take a step back and give myself a chance to see how I want to grow as a photographer and filmmaker, because I’ve been so hyper-focused for so long. The way I’m really going to move forward is to give myself that genuine space. I’m not reading a lot, or watching or being inspired by other things because my face is up against the wall and if I was to start another personal project now I would feel like I’m running from myself. It would be benefit me as a person and my work better if I was able to step back a bit more, rather than just looking from the bridge of my nose all the time.

Christopher is represented by Tea & Water Pictures. You can see more of his work here:

http://www.teaandwaterpictures.co/artists/photographers/christopher-lamarca/

And on his own site: