Urbanisation: changing face of our landscape

More than half the world’s population now lives in urban areas. And by 2050 it is estimated that some 66 per cent will be city dwellers. Mass migration from rural areas forms a large part of this urban population growth, the majority of which is expected to occur in Africa and Asia.

But how countries and cities respond to human mobility is critical to their future and to our planet. Urbanisation is nothing new but it’s the pace of growth that presents the problems and challenges now and for the future.

Many migrants’ moves are unplanned and based on survival; pushed to relocate from the countryside because their rural lifestyle is no longer enough to sustain their family, or forced because of drought or flooding. Others move because they’re encouraged by the prospect of better jobs, a higher standard of living, and access to better education and services. The bright lights of the city, the digital revolution, and what people feel is the pulse of life, also pull people in, particularly younger generations.

Making cities resilient for our urban age and managing this rapid growth in a sustainable, inclusive way is a monumental task. In many situations, among developing countries, basic infrastructure problems first have to be solved. And you only have to cast an eye across the world at its favelas and slums, clustered around the periphery of major cities, to see where inclusive urbanisation still goes wrong.

Photo credit: RUF

Mongolia is one example where the scale of regional migration is phenomenal yet poses real challenges. Every year, tens of thousands of native nomads quit their traditional lifestyle and migrate to the fringes of its capital city, Ulaanbaatar. Its population has doubled since Soviet withdrawal in 1989, with around 20 per cent of the country’s people moving to the city, whose territory has grown around 30 times in size as these nomads resettle and pitch their gers (or yurts) on any available land.

The speed and scale of settlers has disrupted and pressurised the city’s limited resources, challenging employment, healthcare, education and other basic urban services such as heat, running water, waste disposal and sewerage. Arid soil and a harsh winter climate compound the situation.

Non-profit architecture practice Rural Urban Framework (RUF) is one organisation trying to help transform these districts around Ulaanbataar. It believes that urban scale thinking is actually not about large scale at all, but about small scale interventions and the difference they can make.

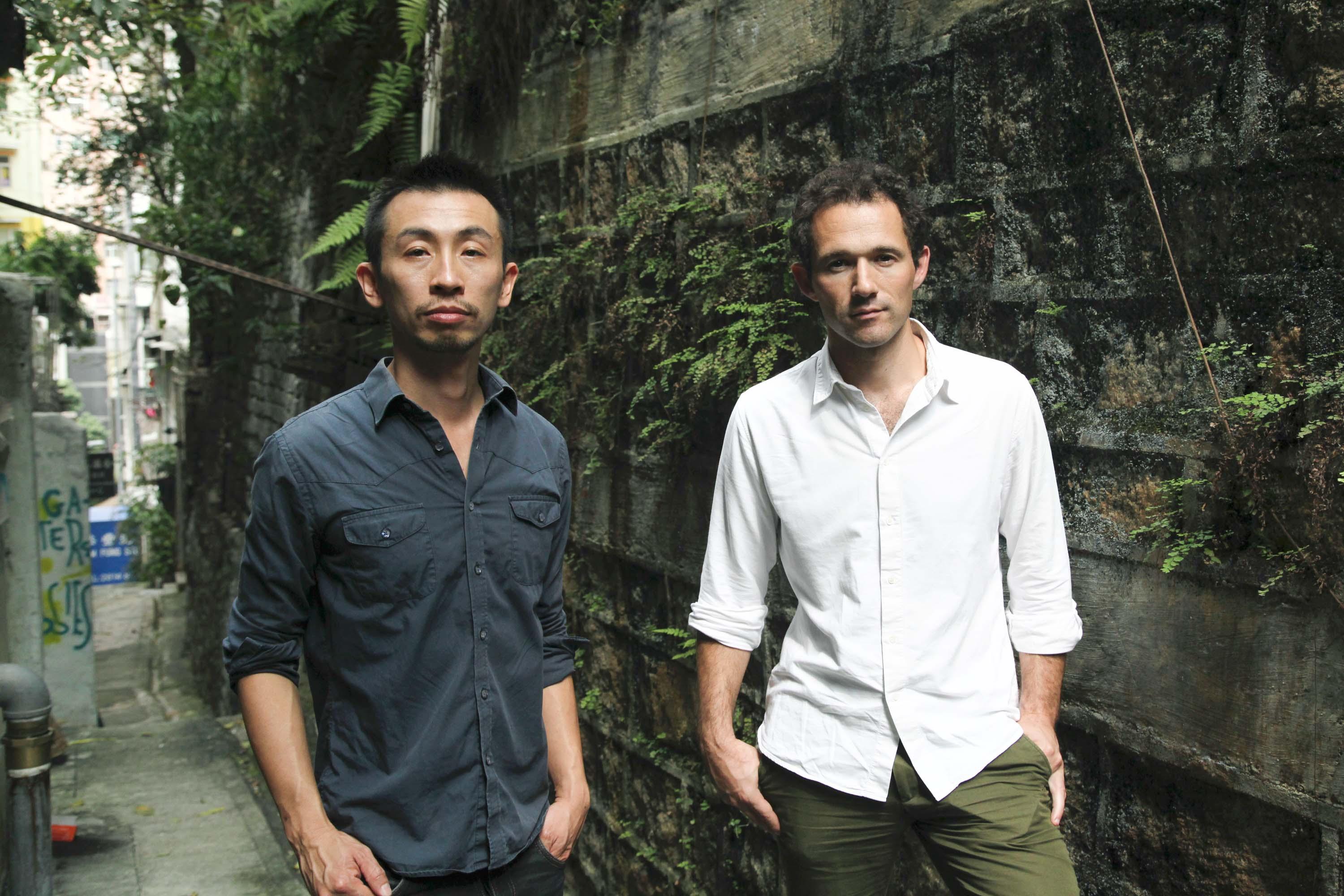

We stumbled across RUF on our recent visit to London’s newly migrated Design Museum, where powerful installation piece City of Nomads, comprising a traditional Mongolian felt ger, is on show until April. RUF, a research and design collaborative between Joshua Bolchover and John Lin, and its local partner GerHub are exploring how the ger – the home of the nomads for thousands of years – can evolve for a more communal, urban life. The lifelike installation, clad in thick felt, considers how several tents might plug in to a central structure for communal amenities and activities.

Photo credit: Luke Hayes

On the installation’s central chamber, videos are projected onto its wall featuring former nomads reflecting on their past and present lives in Ulaanbaatar. One woman describes how in her rural environment “You can just open the door and see the steppe [its grassland ecoregion] stretching out endlessly. You sip your tea as you watch your cattle graze”. Another woman says the capital was once a beautiful city with incredible air quality (now pollution is very bad), and the ger districts weren’t as crowded as they are today. Many young people who can’t afford flats in the city “just build a yurt and settle in any space they can find”, whether on the city’s periphery, residual inner areas or slopes. Another nomad recalls how her family moved to Ulaanbaater from the countryside once their livestock died after two seasons of “back-breaking zud [severe winter]”, a periodic occurrence which is thought to be aggravated by climate change. But life is hard in the ger districts and is getting worse day by day. The pace of migration has meant the basic services of urban life haven’t been viable; water is fetched from kiosks that operate like petrol pumps, pit latrines are dug on site and rubbish goes uncollected.

City of Nomads gives a glimpse at the scope of ideas that Joshua and John started conceptualising a few years ago when they began working in Ulaanbataar. The ger districts are still stigmatised as problem areas, effectively slums that are seen as an obstacle to the city’s evolution as a modern capital, says Joshua.

Photo credit: Camilla Holmgren

“Our aim is a strategy for incremental change that can help transform these ger districts into a viable urban construct; integrated into the future fabric of the city,” he explains.

“Any form of top down planning by government doesn’t work in these areas – the government is bankrupt and the land is owned by the residents so it’s very hard to make anything happen. This is where we like to come in; in these really difficult situations.”

In its most recent world migration report (2015), the International Organisation for Migration blames problems with local infrastructure as a result of rural to urban migration on poor planning. Many city and local governments still do not include migration or migrants in their urban development planning and implementation, it says. This seems crazy.

Joshua says this is clearly not the case in Mongolia where despite its best intentions, and plans, it just didn’t have the money to implement broad scale infrastructure to cope with the influx of nomads. “The government had all these ideas; all these master plans for the whole city, widespread infrastructural plans for sewerage and highways. It has them all. These were originally done by a Japanese organisation then adopted by the [Mongolian] city government, which wanted to implement some of them.

“In the boom years [when optimism followed predicted double digit GDP growth rates in 2011], when I first went to Mongolia, this was what all the talk was about – developing an underground system and these large highways,” he adds.

“But then commodity prices crashed with the global recession. The government had issued all these bonds to try and raise capital to enable it to do these infrastructure projects and now they are very much devalued.

“So it’s had a huge number of economic setbacks and now simply doesn’t have the money.”

Photo credit: RUF

Joshua agrees it’s been a coupling of pull and push factors which has created this huge influx of nomadic settlers. “They have been drawn to the city because they felt it had opportunities but coupled with these terrible winters, which destroyed all the herders’ animals, they really didn’t have a choice,” he says.

It’s also very fundamentally different to other areas, say in China, for example, he says, where RUF has already done a lot of work. “The government made this policy that every Mongolian national had this right to claim the land [an area of 700m²] – it meant each new migrant could own a section.

“So suddenly you have all these herders who arrive and are populating vast areas and when someone then comes along and says “We want to build you infrastructure but we’re going to have to take over your land” of course they’ll say no as this is the one thing they have. So actually to make anything happen is tricky.”

The next option is to look outside to see if big business will commit but Joshua says there’s no incentive now – as developers just can’t make any money. “Negotiating with so many people to buy up their land, there’s no profit margin, so they can’t do anything either. It’s really at this stalemate.”

Another fundamental aspect of rural migration is the idea of community living in these urban ger districts, which nomads are not used to. Their past and present lives couldn’t be more different. For one, they have no prior experience of truly living among others, making it a “unique and urgent situation”, says Joshua. Some say there is no word for ‘community’ in Mongolian.

Photo credit: RUF

“What we assume to be public spaces in the western world and how we conceive of those types of organisations just don’t exist in Mongolia as we would expect,” he explains. “In the rural areas you have all these gers, maybe they cluster in certain areas, but it’s not really a village. It’s just a collection of tents and they move on; so there’s no legacy of things that become stable at any point.

“And then the ger itself, even though that’s the most private space, also becomes the most communal or most public in a way. So the problem is that as soon as it comes to the city and that tent becomes stable and fixed and the settlers erect a fence [from salvaged materials] around it, then these issues of public and private become much more pronounced.”

This ger plug-in that they are building in March this year is an adaptation of the ger to change it to include a kind of local infrastructure. “The idea is that rather than build infrastructure from the top down, you build it from the plot itself, so we’re adding to the ger a type of toilet, septic tank, water collection facility, and shower, which of course they don’t have.”

Photo credit: RUF

They are also creating a more effective heating system to the tents to try and reduce the smog that hovers over the city in the winter months as settlers burn coal to stay warm.

“The idea is that this could also adapt and grow if their needs change into a more permanent house,” says Joshua. “So it’s in between ger and a house.”

Other ways that RUF and GerHub have been able to help include their waste collection prototypes or ‘smart collection points’ – their first project phase.

Photo credit: RUF

When people arrive in the city, they don’t really know what to do with their rubbish because as nomads they didn’t have rubbish. “So you have this huge build-up in the gulleys, in spaces outside the ger plots,” says Joshua.

RUF, which is based at the University of Hong Kong, developed an idea for people to be able to drop off their waste, which could be coupled with a local shop or another facility. Two prototypes were built in Chingeltei and Khan-Uul.

So how has reception been among these nomadic settlers? Each time RUF visits, it conducts community workshops, sharing ideas and chatting to the residents about how they react to certain things. “They are open to change and are actually quite able to evolve and adapt in new situations,” says Joshua.

Away from rapid urban sprawls like Ulaanbataar in Asia and beyond, are, of course, the rural areas left behind. RUF has already built schools, hospitals and housing in villages across China, helping to consolidate rural communities that are being transformed by mass migration to cities.

Joshua says when he and John, who are also both professors at Hong Kong university, started up together more than a decade ago, all the discussion around China was really about the cities – the big growth, the speed of development. It made them think more laterally about the knock on effect in the countryside.

On the one hand you can argue that China’s push for the cities did alleviate huge amounts of people out of poverty and has been hugely beneficial. “People are much rich than ever before.,” says Joshua. “But at same time, people do get left out. So we were looking at what does get left out or what the future of these villages could be.”

In China it’s really about the impact of the urban on the rural, whereas in Mongolia it has been the impact of these rural citizens moving into the capital and the effect this is having on the city itself.

RUF started its first project by going out to the countryside in China to find out what was happening to those villages and how they were being impacted by the process of urbanisation. “We found that there was a real need to try and develop a very low cost architecture that could deliver different types of learning or healthcare environments (such as schools and hospitals) or small infrastructure such as bridges, so we set up RUF to act as a not for profit practice.”

RUF offers all its design services pro bono and works with charities, NGOs and local government to try and realise some of these projects.

Photo credit: RUF

In China, these have included the re-configured Angdong Hospital, in Baojing County, which recently won the Royal Institute of British Architects’ (RIBA) international emerging architect prize.

Photo credit: RUF

Another ongoing project is the Jintai village reconstruction in Sichuan Province, a socially and environmentally sustainable prototype for earthquake reconstruction. Twenty six houses are being rebuilt, including a community centre, using local material, a green roof, biogas and accommodation for pigs and chickens. RUF describes it as an investigation into modern rural livelihood.

Other long term projects include a new school, also with a hybrid community centre and ecofarm, in the poor and remote village of Qinmo, Guangdong Province. It is about encouraging environmental and economic self-sustainability, with villagers able to grow organic products to be sold in the Hong Kong market.

Photo credit: RUF

There’s also the Lingzidi Bridge, in Shaanxi Province, which is designed to reconnect the nearby walnut orchard so that produce can be harvested and transported and the local economy of the villages re-instated. The bridge can also act as a social hub for the village.

Photo credit: RUF

“What’s interesting about doing all this work is that it really gets down to the fundamentals of architecture,” says Joshua. When you don’t have a lot of money, you don’t have a lot of skilled craft, you don’t have a lot of choice for materials and methods of construction, it really becomes about how can you make spaces that allow people to live in them, work in them, and learn in them, in great environments.

“John and I like these limits in order to push what we can try and do with the space we’re trying to make in these areas.”

With their current project in Ulaanbataar, the duo is hoping that if the ger plug-in can truly catch on, then maybe they can prove that it’s possible to really create change on a large scale but through a very small scale.

“For us, it’s about the realisation that urban scale thinking is really not about large scale at all, it’s about the small scale; those small scale interventions could really make a bigger impact overall if they get multiplied, interchange or grow over time,” says Joshua.

For now, this is just a little glimpse into what’s going on in one corner of the world. But with Asia predicted to form a dominant part of the mass migration from rural areas over the next few decades, it’s one corner of the globe that needs more people like Joshua and John.