City spotlight on New York:

Billion Oyster Project

Bringing you our latest city spotlight feature on what sustains cities globally. We look at a non-profit initiative working to revive New York Harbor and reconnect locals to the water and natural environment.

New York was once the world’s oyster capital of the world. Rewind a few hundred years and the city’s harbour was one of the most biologically productive, diverse and dynamic environments on the planet, with around 220,000 acres of oyster reefs. New Yorkers capitalised on this, with oyster barges, street vendors and restaurants ubiquitous for many, many decades. By the turn of the 20th century, every last oyster had been eaten and this once pristine estuary destroyed. It remained toxic and lifeless for more than 50 years until the Clean Water Act banned waste and raw sewage from being dumped there.

Now, Billion Oyster Project (BOP), which has been running for four years, is determined to transform this urban waterside area into a community space to be proud of. Based on Governors Island, the project aims to restore oyster reefs to New York Harbor through public education schemes. It talks of reviving this shared blue space and reconnecting New Yorkers to the water; creating a healthier, happier and more resilient city – one oyster reef at a time. This is a project involving local people, for local people. It hopes to plant one billion oysters in New York Harbor by the year 2035.

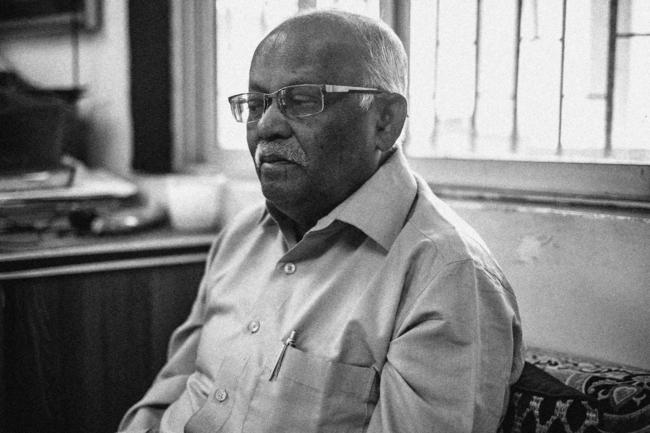

Have a read of our conversation with executive director and co-founder Pete Malinowski, where we find out more about the project and how school children, restaurants and volunteers are very much at its heart.

Photo credit: Micheal McLaughlin

Billion Oyster Project has celebrated four years. The numbers are already impressive: 28 million oysters restored, 19.7 trillion gallons of water filtered, 6000+ local students engaged, 70+ restaurants and 9000 volunteers involved. What message do you have for all these people?

Billion Oyster Project grew out of our flagship school, New York Harbor School. We learnt pretty quickly when we started doing this work that the only way we are going to be successful is if we engage as many of the 8.5 million people who live in New York City as possible. So through our partners, students, volunteers and everyone else who has participated in some way over the past four years; they are our work and we wouldn’t be here without them.

The project’s mission seems so in tune with how Tea & Water feels about cities and what helps sustain them: shared green spaces where people can truly connect, be happier and healthier. Let’s talk more about this.

This is about finding a better future. We’re trying to figure out, in one of most urbanised estuaries in the world, how humans can co-exist with the natural environment and how both can be better for it. We’re never going to have a New York Harbor that we had 400 years ago but we can have one that’s a little cleaner, with more life in it. Living with wild animals is something we want to be able to do in New York City.

With all these global commitments to climate change action, it feels many more people are actually talking about the importance of connecting people to nature and getting them to care about their ecosystems, and how to do it. Tell me how BOP got started and what prompted you to found the project.

Our fundamental thesis is that direct engagement in improving the natural environment is the best way to build awareness and affinity for the resource. It’s not just about seeing wild animals; it’s about playing an active role in making our ecosystem better. That holds true for our collaboration with restaurants, students, volunteers, our own staff and everyone else. In order to restore the ecosystem, you have to understand how it works. You have to understand what animals there are, what harms the ecosystem and how to prevent that. Building investment in your own work and learning – that as an individual in New York City you have the power to have a positive effect on the ecosystem – is the fundamental thesis of BOP.

Billion Oyster Project grew out of the New York Harbor School, where students began planting oysters in 2009 as part of their maritime curriculum. We shifted the student experience from monitoring water quality to playing an active role and actually growing oysters and restoring them. We then started to realise we didn’t just need people to grow oysters, but needed people to conduct research, drive boats, build boats, scuba dive and many other things. So it went from an aquaculture programme to a larger [restoration and education] initiative [in 2014], involving these different disciplines the Harbor School trains students in. Billion Oyster Project also works closely with other schools [more than 6000 local students have been learning through the project’s hands-on curriculum] throughout the city.

Photo credit: Micheal McLaughlin

As you say, it’s about that tipping point – of getting people to care about an issue not simply by being aware but by physically doing. That’s what makes the difference. And you guys are all about the community and people in the community enabling you to accomplish your vision.

What’s so special about oysters for our ecosystems?

It’s useful to draw a parallel with coral reefs. Reefs are complex 3D structures that create habitat (like an underwater city) for thousands of species. There’s a lot of attention and energy going into preserving coral reefs. Oyster reefs do all the same things as coral reefs – they provide food, habitat and shelter for other animals and filter the water and stabilise the bottom. So having a harbour without oyster reefs is just like having a forest without trees or a coral reef environment without the coral. With oyster reefs you lose that three-dimensional habitat and centre for biodiversity. A big difference between tempered estuaries and tropical estuaries of coral reef ecosystems is the density of life. It’s much, much greater in a tempered estuary. So places like New York Harbor are never going to have the diversity of a coral reef – with all the brightly coloured fish. But you can have (and you did have) many more fish. So an oyster reef in New York Harbor can have a greater impact on the number of fish in the ocean than a coral reef ecosystem.

It’s incredible and I think many people are totally unaware of this.

That’s mostly because the fish swimming around are not as brightly coloured!

I’ve also learnt that oyster reefs can help protect a city from storm damage.

Historically, oyster reefs and salt marshes protect land from severe storms. They don’t keep the water out but they break waves. Our oyster reefs are very small, and on their own are not going to protect New York City from storms but they’re part of an integrated solution. An example of this is the Living Breakwaters Project [from the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery (GOSR)]. It’s an innovative $74 million green infrastructure project along the shoreline of southern Staten Island: designed to reduce or reverse erosion and damage from storm waves, improve the ecosystem health of Raritan Bay, and encourage environmentally conscious stewardship of our nearshore waters. Billion Oyster Project will enhance the Living Breakwaters project by installing oysters on and around the constructed breakwaters.

Photo credit: Micheal McLaughlin

How are oyster reefs being restored to the area?

It’s fundamentally similar to restoring any ecosystem. If you have a forest where all the trees are cut down, how do you get them to come back? Plant some seeds and trees, and put some more animals there. We start with what’s limiting oyster success in New York Harbor: the biggest problem is there are not enough live oysters. When oysters reproduce they have a larval stage when they swim around for two weeks before they set. For this to happen successfully you need a critical density of reproducing oysters and you need structures the oysters can attach to, so they don’t sink in the mud and die. And so you can encourage their natural inclination to form reefs by growing on top of one another.

So we build three-dimensional reef structures out of steel and oyster shells. And we put the structures down in areas of the harbour and seed them with live oysters. We’re increasing the density of live, growing oysters and also building these reef structures to act as a substrate for the larvae. A well-developed reef, that’s hundreds of years old, will have a lot of three-dimensional relief. But as we’re starting from scratch, we have to build some of that in to simulate what an older, more developed reef would look like and give the larvae a head start.

So the shells are coming from partner restaurants?

Yes, that’s right – about 70 or so restaurants. These restaurants donate their used shells, so the shells help us to restore oyster reefs rather than ending up in the landfill. The shells are in large, hill-like mounds on Governors Island for a year or more, as being out in the elements helps remove bacteria and organic matter. In our Governors Island hatchery, oyster larvae attach to the shells, and they then join the harbour. We are grateful to Lobster Place, the operator of Billion Oyster Project’s shell collection programme, and the GOSR for funding it.

Photo credit: Micheal McLaughlin

There is quite a lot going on at these reefs. You have community ones (including in DUMBO), which are shoreline accessible and New Yorkers can volunteer to help monitor. And there are also city reefs/structures in deeper water.

For city reefs, volunteers get involved up front, helping us to build oyster reef structures. We recently completed our largest reef project to date, with the help of hundreds of volunteers. Billion Oyster Project was selected by NYS Thruway Authority to construct 422 reef structures for more than five acres of oyster reefs in the Hudson River. Structures went into the water in summer 2018. The goal is to help restore a wild oyster population displaced during the construction of the new Mario M. Cuomo Bridge.

The Billion Oyster Project seems to be all about local communities helping you to construct this ecosystem and in return benefiting from it, in terms of work, education and recreation opportunities.

It is. We see New York Harbor as the greatest and most underused open space. And it’s a resource that all New Yorkers should feel they have a right to access. Everyone has a right to access a clean, biodiverse open space; just as New Yorkers have a right to access New Central Park.

Photo credit: Micheal McLaughlin

That vision – about the importance of shared public spaces and for something great within them reminds me of the Brooklyn Queens Connector (BQX), which has this big plan for opening up the waterfront and creating similar economic and recreational opportunities.

The history of New York and oysters is so fascinating but also sad and inevitable: man’s destruction of nature. But things have obviously changed so much and we are now in a better climate of awareness about how to protect our planet.

That story is such a part of New York’s history but also a part of London’s history. Around 95 per cent of oyster reefs have been destroyed by humans. New York, at one point, was the epicentre for all that abundance and destruction. But it’s a common story. There used to be oyster reefs in all these places.

Back to the public education and schools element. You’re putting kids at the centre of this movement. The importance of connecting to youngsters, to the environmental stewards of the future and of our cities, makes total sense.

We think teaching and learning about the local environment should be a fundamental aspect of every young person’s public school education and we’re working to try and make that happen. In other places, for example in Maryland, learning about Chesapeake Bay is a required aspect of public school education. That’s not true in New York – most kids go through the public school system in NYC and don’t learn anything about the animals that actually live here. And I think that’s a big miss and there’s definitely an opportunity to make the experience of young people more interesting in school. But to also create that excitement, awareness and affinity with the resource that comes with BOP, so students go about the rest of their lives thinking about the environment and their role in making it better.

Photo credit: Micheal McLaughlin

Your passion for education and the environment led you to New York Harbor School – where you started out teaching aquaculture. How do the kids respond to being involved in a real community project like yours?

Students do regularly express to us that the ability to help with a large-scale restoration project is exciting to them. Being able to apply their aquaculture knowledge to a real-world project helps their learning come to life. The fact that it’s a restoration project also helps students to understand that even at a young age (and for the rest of their lives) they can help to change their communities and the world.

Let’s talk a bit about you. You grew up on an oyster farm [Fishers Island].

That experience of learning through doing, where I grew up on a farm, is fundamental inspiration to a lot of the stuff we do. My co-founder, Murray Fisher (from the Harbor School), also grew up on a farm in Virginia. So that thread carries through a lot of what we do.

How does your parents’ expertise and knowledge still inform Billion Oyster Project? Do you regularly converse about what’s going on, any new ideas and so on?

Yes! We rely heavily on my parents as technical advisers for our oyster cultivation.

Are there any podcasts, authors or living figures you’d recommend? Ones that particularly inspire you to keep doing what you do?

There’s a book called Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv, about the benefits of young people accessing nature. The Big Oyster, by Mark Leansky, is a seminal text for what we do. For local environmental activism, The Riverkeepers [by John Cronin and Robert F Kennedy], is a very inspirational book about advocacy.

Obviously you have the restaurants, schools and volunteers involved this project but you also have a really eclectic mix of partner organisations, who make the goals of restoration a reality.

We are a non-profit so we rely on the support of individuals and co-operations to get our work done. And there are definitely a lot of interesting partnerships with experts who come and help out.

Donating to Billion Oyster Project is easy. To support it as a volunteer, educator, restaurant or ambassador, find out more here.