City spotlight on Mumbai:

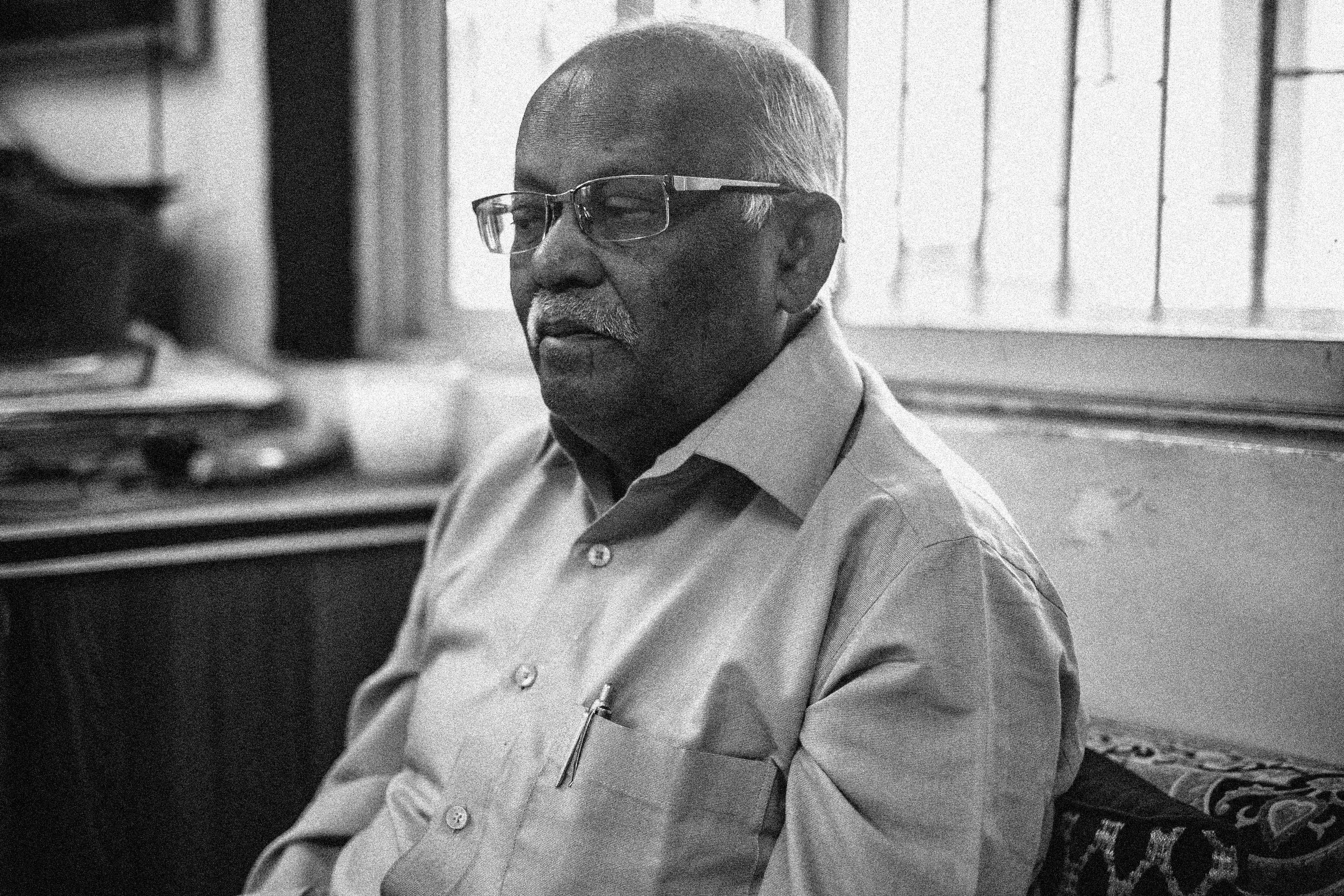

‘slum king’ Dr Jockin Arputham

On the first anniversary of his passing, we look back at the life and work of one man, Dr Jockin Arputham – someone who devoted himself to helping the urban poor with their struggles in India and beyond.

The former president of Shack/Slum Dwellers International (SDI) worked for more than 40 years in slums and shanty towns across Mumbai, India and other cities worldwide. He stood up for the rights of slum and pavement dwellers, fighting to protect their land or get them off the streets and helping with replacement housing when slums were torn down. Through his work, Dr Jockin enabled many thousands of houses and toilets to be built, getting government support for people-centred development.

He is remembered as the ‘slum king’ of Dharavi in Mumbai – a visionary who saw slum dwellers as the lifeline of such a city; the people who keep it moving. He also understood the power of true citizen engagement, and particularly the opportunity for women to make positive change. Dr Jockin believed female empowerment goes a long way in mobilising a community.

Tea & Water co-founder Hannah Vicary recalls one special trip to India and meeting the Nobel Peace Prize nominee, at his home in Dharavi, one of the world’s largest slums. By that time in his life, Dr Jockin rarely gave interviews. We realise what a privilege it was to be welcomed into his home.

India – a place hard to imagine if you haven’t been. It has a magical wonder that greets visitors in so many different ways. Feeling totally overwhelmed is something you never forget the first time you go there. So many people and so many things to soak up in amazement and awe. It couldn’t be more different to life in England. But it is everything that I love about India: absolutely and unequivocally mind-blowing and beautiful. Going back there is always a pleasure, whether for work or just to travel.

This time I was headed to Dharavi, Mumbai’s largest slum. I’ve driven by many Indian slums in the past, always wondering about life behind the makeshift walls of tin and wood, stacked so very tightly, people spilling out onto the streets. On an early trip to India I recall very vividly seeing for the first time a barber’s shop at the edge of a slum in Delhi. In a space fashioned from nothing more than an old crate for a chair and a broken mirror attached to a wall, there someone was – right on the street, having a haircut. Somehow this seemed amazing. It was also my first insight into the deep sense of pride Indian people have in themselves and their homes.

The opportunity to visit Dharavi meant seeing behind those makeshift shacks, snatching a small glimpse at what life is really like. But even then it was difficult to comprehend what a trip there would mean. Even though Dharavi has now become India’s most popular tourist attraction, ahead of the Taj Mahal, we should never forget that it is a place people call home, often for generations. Yet it really is something else – at 500 acres, with a road that cuts through its middle and creeps on for miles.

With no idea of where I was going, I passed Dr Jockin’s address to a taxi driver and hoped for the best. Off I was to meet a man I had read so much about and hugely admired. Someone you might naïvely presume would no longer live in a slum after all the international accolades he had received.

At the entrance to Dharavi stood a tiny temple and a battered old sign, aged by many a monsoon, no doubt. A smartly dressed Indian man in a pressed white shirt stood waiting for me. As I followed him in, the clamour of the city’s incessant auto horns and my nerves at being an obviously western woman alone in a slum fell happily away. Life felt calmer, women passed me in their beautiful, bright saris, children in school uniforms, girls with their hair in bunches.

And there, in a tiny concrete house, sat cross legged on a bench against a window, was an elderly man, Dr Jockin. His sight had clearly deteriorated over the years and I could tell he struggled to see me as he invited me to join him.

As we started to talk, Dr Jockin told me how proud he was to be a slum dweller, campaigning to protect slums and slum dwellers for over 40 years. Yet he was not born in the slums. He first moved to Mumbai (Bombay) from his home in the Kolar Gold Fields, south of Bangalore, in the late 1960s. He was forced to leave home as a teenager because of a lack of food available to him and his family. He knew he had to go and find something better.

Like many of us he found moving to a city incredibly overwhelming. Aged 16, he was living for the first time on the edge of a slum called Janata colony, which has since been destroyed. ‘When I moved to Mumbai, it was a cultural shock for me,’ explained Dr Jockin. ‘Until then I had never even heard of the word ‘slum’. But my situation was very serious at that time – I had no roof on my head, no roots in the city, no relations. So I tried living in a slum.’

It quickly became quite clear to Dr Jockin how incredibly connected a slum community is; the warrens and paths between its homes often just separated by simple pieces of cloth. ‘Here in the slum everyone is attached to each other, everyone depends on each other. It’s like a network,’ he said.

For four years Dr Jockin lived on the fringes. Yet he said: ‘Survival is not a problem. With slum dwellers there is always a smile on their face, all of them are peaceful and happy because they share a life.’ Starting work as a contractor clearing rubbish, he soon created his own company, Lift and Shift, employing other slum dwellers to work for him. Hiring labour to clean the grounds, he became quite well known among the community.

In his early days at Janata colony, there were no formal rubbish collections, which led to mosquito infestations. The local government chose to ignore the settlement, and so Dr Jockin took prompt action. His passion for community action and being a grassroots organiser came easily. Dr Jockin happily recalled a picnic he organised with the slum children, who were invited to turn up with a bundle of rubbish wrapped in newspaper. Early one morning, hundreds of kids were led in a long procession to the local government offices to dump their unopened picnic loads on its doorstep. ‘The whole of the government compound was full of rubbish,’ Dr Jockin recounted. Shortly after this the government began a regular rubbish collection again. ‘It was the first day I tasted the power of community,’ he told me.

Dr Jockin soon found that he was a leader. ‘I would just bring people together and take spontaneous action. I was totally independent and at the disposal of the community,’ he explained.

His attention turned to building toilets, setting up informal schools and establishing water connections. ‘I started to grow leadership campaigning for things like water, literally creating a problem because the state was not doing anything about these things,’ he said. ‘So I would rally all the time and realised I had this power of rallying other people.’

In the 1960s, his first slum home in Mumbai was threatened with demolition. When an eviction notice was served on this colony in 1970, with news that the land was to be cleared, Dr Jockin led the opposition. His protests took him to Delhi, where he squatted outside parliament for 18 days. Dr Jockin was no stranger to drama – arrested many times during his lifetime for all his campaigning efforts. Sadly, this slum was later demolished after all. But the struggle for Janata colony united slum dwellers across the country, leading to the creation of India’s National Slum Dwellers Federation.

As his life continued in the slum, Dr Jockin said he became more and more aware of a war between the urban rich and poor. He was confused about how the outside world seemed to shun the very existence of slum dwellers or mislabel them as lazy, when it felt so clear to him that these people are what keeps a city alive. They often do the jobs of taxi drivers, cleaners and general menial tasks that no one else wants to do. Dr Jockin called them ‘the lifeline of the city, the people that keep it moving’. He campaigned tirelessly and engaged with government authorities to breakdown negative stereotypes and make people understand how important slum dwellers are to the fabric of cities like Mumbai, to sustainable urbanisation.

Dr Jockin’s life’s goal was to get everyone in Mumbai at least off the streets and into a slum. He wanted to make the city and other similar places ‘slum-friendly’ – to turn slums into places with proper drinking water, proper toilets and schools. In Mumbai alone, one of the world’s most densely populated cities with more than 22 million inhabitants, around 200,000 people are homeless and more than 40 per cent of people are officially said to still live in its slums, though many believe this figure to be higher.

Working with Mahila Milan (a collective of savings groups formed by female slum and pavement dwellers) and Mumbai-based NGO SPARC, the National Slum Dwellers Federation offered city and state governments all over India partnerships for slum redevelopment, so that many thousands of urban poor people could access housing and sanitation.

Despite its difficulties, life somehow feels more alive in a slum, in Dr Jockin’s eyes. ‘Everyone knows each other’s story,’ he told me. Life in this community works well for so many people because it truly is about them, he explained. The ‘beauty of the slums’, Dr Jockin called it. A place where ‘the poor are smiling, while those on the outside worry more’. Dharavi dwellers may be poor, and squashed into the heart of India’s financial capital, but their community is also a thriving hub of action, with an estimated 5000 businesses and 15,000 single-room factories.

Much of the industry is powered by women, whom Dr Jockin talked a lot about during our conversation. He saw them as the soul of the slums, keeping these communities together - and the ones to mobilise a community. Dr Jockin’s own journey over the years is also a story of female empowerment. He did so much to help women over the years, first starting a women’s group in Dharavi, a focus that later spread to many other slums. ‘I saw in the beginning, the importance of the roles of women, not the men,’ Dr Jockin explained. ‘So I began work gathering women together.’ Around 300,000 women in Dharavi joined this group. This sort of number meant getting the government’s attention got easier, he said. But this was about creating ‘peaceful’ problems. ‘I rallied people all the time – it made me a popular character in the slums.’

Dr Jockin agreed that if many more women around the world growing up in less developed places could be educated, then the world would shift in a much more positive way. He told me that as his community efforts continued, he looked at three elements a slum community needed to survive and prosper: money, information and communication. ‘All of it came from the women. I found these strengths and used them to build the women into a collective sense.’

The women are the sharers of information, the keepers of money and are the ones who naturally communicate with everyone, explained Dr Jockin. He also felt it was wise to engage the women, as they are the ones with the ‘natural nurturing instinct’ to truly protect their family, their neighbours and their community.

In his early days living in a slum, Dr Jockin found it was always the women who would reach out and offer him a place to sleep. It was the women who knew everyone’s business. And it was the women who all communicated with each other; passing and sharing so much information. So he realised they would be the ones to help on a mission to fight the government for slum dwellers’ rights. It was their participation he knew could make some change. ‘Women can do real citizen engagement,’ said Dr Jockin. ‘They are the leaders.’ He added: ‘We have had many rallies and I always wanted everybody to be very peaceful’ – another reason he felt it better to engage women over men.

Yet he quickly realised how men dominate financially within the home: while women earnt money, familial dynamics meant they would never stand up to the men demanding the salary be handed over, often to be spent unwisely. The whole premise of a women’s group, Dr Jockin explained, was that if slums were displaced, he needed to empower women enough to set up their family elsewhere or at least purchase vital clean water and other basic supplies. Of course many of these slum communities in Mumbai were destroyed over the years. So he needed to create a means for women to save part of their wages without going against their husbands. This was done through savings schemes, set up by Dr Jockin to enable women to contribute small amounts of their wages to a system that would keep the money safe. ‘Most important is empowering women,’ said Dr Jockin.

There are now thousands of slum-dweller-managed savings groups (more than 15,000) operating through Slum Dwellers International (SDI) in cities around the world – with an estimated 14 million people currently participating in these groups.

SDI was co-founded by Dr Jockin and it comprises a network of community-based organisations of the urban poor in 33 countries. It is through the SDI that land has been secured over the years for thousands of families, enabling all these houses and toilets to be built.

These ‘federations’ of slum and shack dwellers extend beyond India to elsewhere in Asia, Africa and Latin America. They support and learn from each other – using the global SDI platform to help local initiatives. And so Dr Jockin’s early passion for community action, for being a grassroots organiser never left him - it just went global. And it went global with the help of many, many women.

Towards the end of our conversation, Dr Jockin mentioned how easy it would have been to move to a richer community once he had made a name for himself. But he said: ‘There is no soul or spirit in how the people live. They do not know their neighbours, there is no support [system].’ To me, sitting there with Dr Jockin, as he answered calls to his phone and conversed with the women who popped into his home, he really did seem to embody the soul of what it means to be a true neighbour and community citizen.

This insights piece is part of our spotlight series on what sustains cities globally, in this case the extraordinary efforts of one man who protected the rights of so many people living in urban poverty.